Mind the Gap! —Guidelines for Interviewing “SESL” Candidates

You thought that the last job applicant you interviewed who was a Speaker of English as a Second Language (what I shall call an “SESL” for short) understood everything you said because you understood everything she said.

Or, you thought another SESL applicant understood very little of what you said, because you understood very little of what he said.

Or maybe you thought the applicant could (not) write or read English well because he or she could (not) speak or hear it well.

Or perhaps you thought the applicant could (not) do the job very well because he or she could (not) clearly and accurately explain, in English, what the job involves.

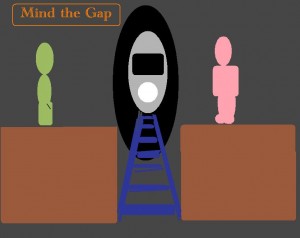

Digging Your Own Language Pit

When interviewing an applicant whose first language is not English, there are pitfalls like these that you need to be aware of created by the gap between

1. how well the applicant speaks (or otherwise performs in) English and how well she hears it (or performs in the remaining forms of English communication)

2. how well you think the applicant can do anything (in English) that you have not tested, sampled or otherwise elicited and how well the applicant can in fact do it—when the judgments are based primarily on how well the applicant communicates with you in English.

Unless you “mind the gap” (an initially puzzling Big Brother warning I first heard on “tube” platforms in London, whenever the train doors opened), you may unwittingly widen it or disastrously and erroneously think you’ve bridged it.

Even if you have substantial second-language/second-culture experience, you may be at risk of committing some of the most common and costly language-based mistakes—e.g., equating the better (or the worse) of a candidate’s speaking skills with her other unconfirmed listening, writing or reading skills, or vice versa.

Odds of Gaps

This kind of fallacious inference about communication skills is an extremely likely mistake. Many very capable job applicants will have huge but undetected gaps between and among these skills, for example, often being able to express themselves quite decently in conversation, while lacking commensurate listening skills.

On the other hand, if you have had to deal with your own second-language gaps, you will be more likely—but not certain—to spot them among applicants.

(I am one among such gapped polyglots: I read Mandarin much better than I hear it, e.g., I was able to translate most of the conversation-level texts I used in some of my university and college teaching in China, but still can’t understand what any 6-year-old Chinese child says to me.)

Others may have the reverse problem—an ability to comprehend what they hear that dwarfs what they can say, read or write. You must allow for this possibility when interviewing applicants whose primary professional use of English has been, for example, face-to-face or phone-to-phone in sales, rather than in writing for research projects or editorial departments. They may very well hear and speak English much better than they can read or write it, or vice versa.

Ni Hao Well You Speak Chinese!

An extreme illustration of such misunderstanding and mis-estimation, common in the daily life of any traveler, and probably very common in international recruiting situations—like some of those I found myself in, is revealed in the response elicited by merely saying a single phrase in a host-country or culture’s language.

You say, for example, “Ni hao ma?” (“Hello, how are you?”)—the only thing you know how to say in Chinese—to a shop assistant in any Chinatown, to anyone in a real Chinese town or in a meeting in mega-metropolis Beijing, and you may very well hear in reply in English or as its Chinese equivalent, “Oh, you speak Chinese very well!”—as many of you doubtlessly know from similar first-hand experiences of this sort in China or elsewhere overseas.

Of course, often that’s simple flattery as a form of hospitality. Other times, it’s a sincere over-estimation of linguistic competence. In the latter case, the native speaker will often proceed to race past the comprehension of the non-native speaker (“NNS”) with a barrage of fast-paced, idiomatic and otherwise difficult talk—something I saw happen in the daily staff meetings I participated in as a newspaper editor in Hong Kong, where both Chinese and non-Chinese staff did that.

Too embarrassed to beg for a pause or clarification, the NNS smiles and nods—just as an SESL job applicant may if you use what are for you perfectly clear idioms, such as “At the end of the day, I wouldn’t slot you into that dead-end job for all the tea in China”. (The panicked SESL’s translation: “By 5 pm today, I won’t bury you in a grave at that grave-digger’s job that pays you in Chinese tea, rather than money—even though it’s an incredible amount of tea.”)

Nod a Good Idea

The smile-and-nod example illustrates one pitfall to be alert to in your own cross-cultural interviewing—utterly reversed body language, when a nodded “yes” (“I understand you.”) means “no” (“I don’t understand you at all!”). Don’t mistake smiles and nods for comprehension.

In less casual, more professional contexts, this kind of misunderstanding and over-estimation can wreak havoc—just as the flip-side linguistically-induced under-estimation of an applicant’s communication and other skills can. For example: You imagine the NBA’s Yao Ming doesn’t know his play book because he can’t explain it to you in English.

The Questions to Ask

There are diagnostic questions you, as a recruiter, can ask to determine whether you are facing such a gap in any given cross-cultural interview. With respect to an “oral-aural” (speaking-listening) gap, one such question is this: “In achieving your (excellent) level of spoken English, which method worked better for you—reading, or listening?”

This question can help you determine whether the applicant’s strong or preferred method of language-learning input is visual-text or auditory. (Other possible gaps can be investigated by using comparable questions adjusted for the communication modality, e.g., writing vs. reading, or speech vs. writing.)

You can use the response to your question to do two things: to attempt to divine how that applicant’s learning preference correlates with her listening comprehension, or, more simply, to use that first question as a lead into a second: “How does your English listening comprehension compare with your speech, reading comprehension/speed and writing abilities?”

Of course, if it is evident that the applicant has a well-balanced language skill set, there will be no need to ask. But it is important to know what counts as conclusive evidence of this balance when smiles and nods do not.

To ignore such differences would be tantamount to assuming a bilingual candidate for a PR job would be a great interpreter in a press conference just because she is a great translator and smooth talker. Big mistake.

More Mis-Estimations to Avoid

Underestimation of an applicant’s communication skills or even her intelligence is very likely if you assume her best untested, unrevealed performance abilities will be no better than her worst displayed ones. For example: Inferring that a candidate’s English or other writing or reading ability must be poor because either her listening or oral communication is not up to snuff would be an error. This is a variant of the Yao Ming blunder.

A clear illustration of an oral-aural pitfall is the fact that many Japanese do not hear question words at the beginning of sentences, such as “who”, “why”, “when”, “where”, and “what”—because in Japanese these words do not come at the beginning of a sentence and are therefore not expected or noticed by them as consistently as they are by native English speakers.

Hence, if you ask a native-Japanese speaker who has this “deaf-spot”, so to speak, “When did you leave your last job?”, he may reply, “yes”, meaning he did leave his last job—because he heard you say, “Did you leave your last job?” So, to compensate for this, you may want to stress the first word in questions, but without sounding patronizing, e.g., “Whendid you leave your last job?” In any case, make it audible and don’t slur it.

Dim Summing Up

To sum up the guidelines:

- Do not assume that high/low-level oral communication confirms high/low-level listening skill (or writing or reading).

- It is probably safe to assume that excellent skills in all four modalities—speech, writing, reading, listening—are strong evidence of high-level intelligence. However, it is very risky to assume that a lack of one or more of these skills equally corroborates a lack of intelligence. Don’t do it.

- Make sure your cross-cultural interview and presentations have both visual (e.g., written and/or image-based) and listening elements, for the sake of helpful redundancy and engagement.

- Do not depend on agreement-displays in body language as evidence you’ve been understood.

- Considerately compensate for differences between your native language and that of the NNS, without sounding patronizing. If you frequently deal with a specific language category of SESL, e.g., Chinese or Russian, make an effort to get acquainted with some of those differences so that you can deal with them.

…Follow this advice and no one will mistake you for a dim somebody.