Slices of Life and R3: The Art of Reading Career Salami

For example, to make it past the first cut in an interview, an applicant has to provide two cuts of his or her life. These are: a “personal history” slice, which is the “longitudinal” (lengthwise historical “career salami” cut) and the current “cross-sectional” (fixed-time breadth) cut that reveals all the things the applicant is capable of or doing right now, or, if sliced farther back, was capable of or doing at some specific earlier time.

What makes it important to be aware of these life-salami slices and how they differ is that bad screening decisions may result from

- mixing them up

- wrongly choosing them as specific samples

- ignoring them

- overestimating the significance of the slice in hand

- otherwise being fooled by the ones presented by or taken from the applicant

- assuming they are they only two dimensions that matter.

In particular, the slices may have been cleverly and misleadingly selected and presented by the applicant, or do not capture the applicant’s “depth” (professional or otherwise) very well, if at all—and then, only by (shaky) inference.

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Slicing of the Salami

In terms an historian, geologist or biologist could apply, these two kinds of slices represent the historical, longitudinal (d)evolution or piled-up strata of the applicant over time and the snap-shot cross-cut (mal)adaptations, distinctive attributes and capabilities at a specific time (past or present).

Instinctively, recruiters will take a close look at both kinds of slices. However, there are obvious dangers in doing (only) this. These mistakes include

- mistaking one cross-sectional slice for another earlier one (or vice versa),

- overemphasizing longitudinal continuity at the expense of cross-sectional breadth and variety of experience

- taking a misleading slice or in making shaky inferences from one slice to another, e.g., inferring that because an applicant was effective and happy multi-tasking last year, (s)he hasn’t burned out since then.

Likewise, there is the comparable danger of mistaking one longitudinal slice for another or having one such lengthwise slice cunningly carved by the applicant to emphasize his or her personal best in some single gap-free dimension, e.g., continuity of personal development courses as a timeline and yardstick, in order to mask gaps in employment, career dead ends, etc.

To get a good idea of what’s in a salami, you have to cut it across and lengthwise. The same, and more, goes for job applicants. In both the case of a salami and a job candidate, the more slices of both sorts in hand, the more accurate the information to be trimmed from them, since the more numerous, larger and random the samples, the surer the inferences from them.

As noted, what this “slice and slide model” (on analogy with microscope slides as well as salami slices) doesn’t capture is “depth”. For example, it misses depth of technical expertise (the capacity to deal with technological subsystems embedded within subsystems), “tree depth” as twigs on the branches and trunks of knowledge and information, or “nested “knowledge (extensive knowledge of categories within categories). Knowledge of this latter sort is illustrated by knowledge of not only species of oil-producing plants but also of the varieties within those species.

Although you can fully grasp the timeline and breadth of a job candidate, you may yet remain in the dark about that candidate’s depth.

R3and “Depth”

A slightly different model may help provide a framework within which to characterize and mine the missing “depth” dimension.

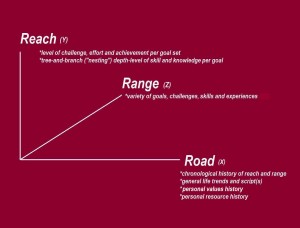

In developing a therapeutic conceptual model for the Focus Foundation of B.C., an integrated program of services for at-risk children within the province of British Columbia, I recommended (and won acceptance for) what I called an “R3” model (on analogy with the symbol for 3-dimensional space of real numbers), a 3-slice framework in which the three key variables to be monitored and fostered were “reach”, “range” and “road”.

Part of what “reach” designated is the extent to which a child (or an adult) has stretched himself or herself by setting goals toward which (s)he perseveres. (In fact, “slice” is a misnomer here, because the three “cuts” in the “R3” model are variables, which, as such, demonstrate the limitations of the kind of simple 2-slice salami model that can overly influence and limit personnel assessment.)

What we call “over-commitment” or “stretching oneself too thin” is the process of attempting to achieve too much depth in too many domains at the same time by setting too many goals and digging too many holes. In (mathematical) space, this can be called the vertical “Y-axis”.

A job candidate may have presented a great professional chronology with no gaps and a broad cross-sectional profile of multiple skills and commitments, but may still lack depth in some key areas because of such over-commitment, by having met a standard that required little depth, or simply by (almost) being out of his or her depth.

If a 2-factor salami model is employed, i.e., without a depth dimension, these weaknesses or blanks may easily be overlooked. In terms of the R3model, the salami-sliced candidate’s longitudinal road and cross-sectional range, however impressive, may not reveal his or her reach (per goal).

“Range” (the z-axis) designates breadth or a cross-sectional slice at any given time. Guiding, advising and assessing anyone—child or employee—ideally should involve careful consideration of that individual’s range of aspirations, experience, competencies and challenges (including “complex needs”).

Finally, “road” (the x-axis) most closely translates into the “longitudinal” historical slice that reveals the actual path taken over time. The thicker that slice, the more of the “range” it captures.

Elements of that road include the timelines for the reach and range, the path personal values have developmentally followed, the history of the resources available, utilized or misused by the candidate, and the general life trends, cycles, patterns, scripts, etc., that characterize the path taken.

“Road” also includes the history of personal values development, e.g., social, environmental, character and relationship standards, which although underlying the goals of “reach”, are distinct from them, much as cause is distinct from effect.

Framing the vetting and interviewing process in terms of R3 assures that the depth dimension will not be overlooked. This means identifying “reach” as the level of challenges engaged, the depth (understood in terms of “embedding”, “nesting” and “trees”) and the level of effort and the level of achievement in taking each one of them on.

The higher the level of achievement per challenge, the greater the level of overall depth for the set, although hard-earned mastery of many single challenges involves little depth, e.g., pitching horseshoes. That is to say, effort and total time invested should not be confused with “depth”. Accordingly, the temptation to use length of commitment with depth of commitment should be vigilantly resisted.

The Limitations of Salami Slices

Lacking a clear analogue of the “reach” dimension, the salami model simply doesn’t cut it as a vetting framework and should be used only with that understanding.

It can, however, be useful in vetting candidates who need to have a history of multi-tasking with diverse skills that don’t require much depth, e.g., jobs with very short training periods and virtually no periodic “professional development” requirements.

But even in such instances, the slices presented by the applicant need to be multiple, truly representative, complete, free of cunning and comprehensive, lest they represent something quite different.

Baloney.