Should Recruiting Operate More Like Casinos?

Can a successful casino-business model be applied to recruiting and to ordinary restaurants?

Dining Roulette

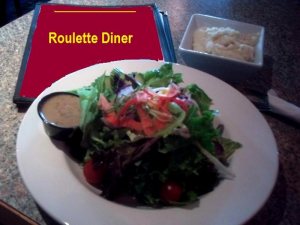

I say the restaurant was like a casino because ordering the dish I initially liked turned out to be a gamble both times: the first time, when I wasn’t sure how big or good my salad would be, and the second time, when it was much smaller and visually less appealing than the pleasantly surprising first one, shown here, in a photo I took (and altered slightly, to better reflect the facts). To be fair to my server and to explain why it was a gamble the second time as well, I should mention that after I offered my appreciation for the debut salad, she did warn me that the size seemed to dramatically depend on which chef was on duty.

What makes this “casino restaurant” worth mentioning is that it invites two questions

- Why is gambling very attractive in some business formats (e.g., casinos), but utterly repellent to or otherwise only reluctantly tolerated by management, employees, client companies and/or clientele (e.g., me, in the restaurant) in others?

- Would expansion of the gambling element in recruiting or in the workplace increase or decrease the odds of recruiter, client company or employee success?

Casino Features of Recruiting

It can be argued that such an expansion of the role of gambling in the job market would merely be an enhancement of the gambling-like features that already exist within them. Job applicants are in an obvious way like Las Vegas gamblers: Each one of them expects, or at least thinks it’s reasonable to hope or expect to be a winner.

They are also like gamblers because most of them are certain to lose on any given day. Moreover, many share the belief that they have a “system” that will improve the odds, e.g., add luminescent graphics to the resume, and make more cold calls than hot ones.

Finally, like the desperate or starry-eyed hopefuls who fly, drive or bus great distances to the bait and promise of Las Vegas casinos, countless job applicants these days have to demonstrate a willingness to undertake a personal hajj or Crusade, if not outright migration to distant places, to get an interview and a job.

In one respect, however, Las Vegas gamblers are better off than job applicants—and not only because when the gamblers win, they often win big and stop working, whereas when job applicants win big, they are just starting. Gamblers are also better off because, theoretically speaking and depending on the game, they can all simultaneouslybe winners, e.g., at the slot machines and roulette wheels (if everyone bets on the same number).

To put it in a slightly more complex way, applying for a job is always a zero-sum game, since somebody has to lose in betting on and applying for the same job, while at a given roulette wheel on a given bet, it is possible for everyone to win, by betting on the same number.

That’s pretty much where the similarities between being a recruiter and a croupier begin and end. But that’s also where some really interesting issues arise. One of these is the main casino technique of client behavioral management

When “Intermittent Reinforcement” Means Steady Profits

Casinos thrive because they utilize one of the most powerful behavioral reinforcement techniques known to and used on man: “intermittent reinforcement”. Slot machines are both hugely profitable and popular because they are designed to neither always pay off nor never pay off and to pay off unpredictably. It is this unpredictability of (huge) payoffs that, as the intersection between the agenda of casino operators and that of gamblers, makes gambling addictive and profitable. If the payoffs occurred more frequently or never, the casino economy would be unsustainable, without serious downsizing of the payoff or the casino meals to compensate for the increased frequency (zero payoffs being a plainly dumb idea).

Longstanding research has shown that intermittent reinforcement is, in some situations, the most difficult to resist—the behaviors it reinforces being the most difficult to extinguish as habits. In that sense, it can create one of the features of addiction. (For example, aren’t you more likely to be shocked, disappointed and alienated by the always-nice boss who suddenly screams at you for the first time than by the usually-nice boss who occasionally does?)The behaviors intermittent reinforcement controls can be more resistant to “extinction” than “fixed interval rewards” (payoffs that come at fixed intervals of time, e.g., an hourly wage) or “fixed ratio rewards” (payoffs that come after a fixed number of tasks have been completed, with or without repetition of any one task).

Illustration: an employee who works for an unpredictable, big commission, e.g., real estate agent, is much less likely to quit his job just because his efforts are not predictably rewarded, than an employee on a “fixed interval reinforcement schedule”, i.e., an hourly worker who doesn’t get paid at the end of the month.

Likewise, an employee on a “fixed ratio reinforcement schedule”, e.g., piecework, is much more likely to walk out or seek redress if not paid what he is owed for the tasks completed on schedule.

True, the real estate agent is also likely to quit or sue if not paid when the commission is due; however, the point remains that because the commission is not guaranteed on either an interval basis or number-of-showings (ratio of effort to reward) basis, the real estate agent will persist and continue to work despite the unpredictability of the timing or of the amount of work required to get paid.

Why Casinos Have to Gamble on Gamblers

Casinos are successful, i.e., money makers, because they work on the principle of intermittent reinforcement—much like the real estate agent’s industry: unpredictable, but big payoffs. Were casinos to switch to variable interval or ratio reinforcement schedules for their patrons, they would either

- Go broke because gambler winnings would be paid out too frequently—e.g., after a too-short interval in front of a timer-driven slot machine or too-small number of pulls on slot machine handles, or because the intervals and ratios would be too large to satisfy their patrons.

- Have to make the cash prizes smaller or dramatically ramp up the perks, such as the buffets, entertainment, accommodation and the transportation vouchers.

Moreover, if the casinos switched to a fixed ratio reinforcement schedule, e.g., pull 100 times and win, gambling would become a job. If they switched to a fixed interval reinforcement schedule, e.g., wait one hour for a prize, gambling would become welfare. Instead, they use “variable ratio reinforcement schedules”—bet or pull the slot-machine handle an unpredictable number of times before eventually winning something. More importantly, using any fixed ratio/interval reinforcement schedule would destroy one of the main magnets that draw gamblers: the excitement of unpredictability and risk, somehow a reward in itself (a kind of “meta-reward” above and beyond the conventional cash rewards).

Gamblers vs. Workers

It is in this sense that gamblers are so different from workers: Gamblers thrive on unpredictability of reward; employees generally hate it, the main reasons for the difference being

- The gamblers’ collectively occasional huge payoffs, in their minds, justify their unpredictability—the unpredictability of both the timing of the payoff and the maximum length of the wait). This is a special case of “utility-driven” persistence (“utility” meaning “payoff”), in contrast to the “probability-driven” (likelihood-of-reward-based) persistence of workers, who, in general need the guarantee of absolutely or nearly certain payoffs at predictable intervals or effort/reward ratios.

- Employees in general—including those who work in real casinos (as opposed to those who work in Wall Street casinos) and probably most real estate agents—do not find unpredictability of payoffs exciting, in part or perhaps mostly because their creditors don’t. Addicted, compulsive gamblers who, from disinclination or inability, pay neither their gambling debts nor their water bills can therefore, despite their dire financial straits, psychologically more easily afford the excitement that would, for someone with a job, be experienced as paralyzing fear.

For these reasons, it is highly unlikely that the recruiting industry will or should expand its casino features beyond those currently entrenched in it, e.g., the unpredictable, intermittent reinforcement of job interviews/offers and commissions. Ditto for the menus and operations of roulette diners.

In any case, there is one defining priority of casinos that most recruiters, their clients, their applicants and employees won’t and shouldn’t ever adopt: giving priority to the redistribution of (gambler’s) real wealth rather than to its creation.

…Wall Street wolves being exceptions that will, even though they shouldn’t.

Image: “THE HOUSE (SALAD) WINS/Image: Michael Moffa”