The Pepsi Challenge Approach to Recruiting

“More than 50% of Coke drinkers prefer Pepsi to Coke” — Pepsi’s trumpeted results of the now-classic “Pepsi Challenge”

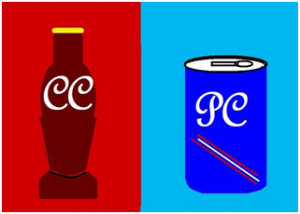

What if one of the most successful soft-drink marketing campaigns of all time could be replicated in the realm of recruiting to promote clients, recruiting firms, individual candidates or recruiters? The well-known, long-running “Pepsi Challenge” to Coca-Cola may, with some minor modifications, be adapted to marketing recruitment related services, client companies (in selling them to candidates) and even individual applicants and recruiters.

A Trip Down Marketing Memory Lane

To refresh or acquaint your memory, a brief summary of the original 1970s Pepsi Challenge should suffice to set the stage for demonstrating its applicability to recruiting. Sophisticated and once ubiquitous—in shopping malls and on street corners, The Challenge involved inviting pedestrians and shoppers to pause and sample Pepsi and Coke in a taste test in which the two cups were labeled “Q” and “M”. The test was “single-blind”, meaning that the presenters knew which cup contained the Pepsi, while the sippers did not.

Presumably, the choice sequence was consistently random—which it was on occasions I did the test, which it would have to be, in order to rule out a one-sided, biased aftertaste influence. To be unbiased, Coke would have to be on the right as often as it was on the left and taste testers would in every instance have had to be free to choose whichever letter or side they wished to choose first.

The result that Pepsi proudly announced was that “more than 50%” of the taste-testing participants who had identified themselves as loyal Coke drinkers actually discovered they had chosen Pepsi instead of Coke as their first choice in the taste test.

After that campaign, which was launched in the Dallas area in 1975, Coca Cola’s 3-1 sales margin was quickly whittled to 2-1.

Fabulous marketing! So, how to apply it to recruiting? Here is one scenario, using an identical format:

Creating a Recruiting “Pepsi Challenge” for Your Client

An applicant is balking at working for a certain company, your client company—let’s call it “Q”. It’s a great job, the company seems interested in him, but he has his sights set on a different company—let’s call it “M”. He’s not alone—for some reason company “Q” is consistently a harder sell than company “M”, which is not your client, and what you are hearing from him you’ve heard before.

So, what you do is arrange for all applicants who apply online to complete a short survey that consists of a side-by-side comparison of both companies’ details, e.g., capitalization, benefits, salary ranges, promotion rates, sales, stock performance, etc., with each company in the survey being identified only by the letters “Q” and M”. The survey can be rationalized and packaged as a diagnostic tool to determine applicant preferences and to facilitate optimal placement.

After the survey is completed, the applicants are to be asked which of the two companies—now identified by name rather than by mere letters—they would normally say they would prefer to work for. When those results are tabulated, they can be used to promote company “Q”, if they show the same trend as the Pepsi Challenge, namely, that more than 50% of the applicants who declared they preferred “L” to “Q” before the survey switched in the survey—suggesting that perhaps their initial pre-survey preferences were not based on the core facts and real preferences, but perhaps on something else, such as a fabricated cool image, e.g., the streamlined shape of the Coke bottle.

Obviously, if the result is not so favorable, you will ignore the survey and try something else. However, if Coca-Cola’s criticism of the Pepsi Challenge was correct, the results will indeed be favorable to the company you wish to back—just as long as you call it “M”, rather than “Q”. The Coca-Cola complaint was that the Pepsi Challenge had a bias: Coke maintained that the taste testers, consciously or otherwise, did not like the letter “Q”.

Very Qurious

One reason given for this aversion is that most English words that begin with “Q” have pejorative, negative connotations, as the very first entry in my Merriam-Webster dictionary, “Qadaffi”, foreshadows and the quickly following “Q-fever” (a mild illness induced by tick bites, so-named because its cause was unknown, leaving the “query” unanswered for a long time). After these, there await “quackery”, “quarrelsome”, “queasy”, “queer” and, of course, “quidnunc” (a busybody) and “quixotic”. On the other hand, go ahead—try to find a positive-sounding “meliorative” (opposite of “pejorative”) word that begins with “q” There are virtually none—save for “qualified”, “quick” and “quokka” (a kind of small wallaby).

The Coke vs. Coke Challenge

Sure of their footing, the critics at Coca-Cola ran their own experiment and gave taste-testers a choice between Coke and Coke. Again, “Q” won, despite the fact that the participants were sampling the same drink twice. In response, Pepsi relabeled the drinks “S” and “L”. Pause: Ask yourself which letter you like more. “S” won in the same way. The Coca-Cola skeptics responded in the same way: There is a bias against “L”, which was the label for Coke in the revised experiment. (It was also argued that the quantities sipped were too small to reveal that Pepsi tastes cloyingly sweeter than Coke when full bottles or cans are drunk. Hence, it was suggested, the preference reversal in the artificially short sipping tests.)

But, suppose that both Coca-Cola and Pepsi Inc got it wrong. Suppose that they both missed, or at least suppressed, the real reason for the “more than 50% switched” figure. In particular, suppose that there is no difference between Coca Cola and Pepsi, just as there was no difference between Coke and Coke in the Coca-Cola challenge to Pepsi.

What a Difference No Difference Can Make

If there is no difference between not only Coke and Coke, or Coke and Pepsi, but between any two things whatsoever, then the statistical results should display randomness. If I ask people to choose between two identical beach balls and place them randomly beside each other (to offset any right/left-handedness bias), and then examine the choices of a subgroup defined by some criterion, e.g., married or earning more than $40,000/year, the result should be that approximately 50% of that group, or any other group, will choose ball #1, rather than ball #2—and vice versa. It’s like putting your hands behind your back and asking participants to choose a hand to find a candy in one of them. If there is no handedness bias, the result will be an approximately 50-50 split in the whole population and therefore a virtual 50-50 split in any subpopulation (which is what the Pepsi Challenge result of “more than 50%….”, e.g., 50.4%, will reflect if the two drinks are mostly indistinguishable.

Notably, Pepsi seems not to have addressed the question of whether 50% of the declared Pepsi drinkers discovered they had chosen Coke in the taste test. If that result had obtained and been announced, there would have been clear evidence that the taste-testers couldn’t distinguish the two drinks.

Add-Ons for Your Recruitment “Pepsi Challenge”

The implication for you, the recruiter, is that if you are dealing with applicants who have a clear preference for one of two virtually indistinguishable companies, you can run the online survey and be virtually certain that you will get the same result that the Pepsi Challenge yielded: 50% of those applicants who maintain they had a strong prior preference for company “X” will in fact “switch” to your client “Y”. That’s what you tell the recalcitrant applicant who resists your job recommendation.

Another valuable lesson to be extracted from this battle of flavoring extracts is that the packaging sells the product, not vice versa. Studies suggest that soft-drink preferences are shaped by “extraneous” factors that include the shape and coloring of the bottle and packaging. One study showed that when 7-Up labeling featured a particularly intense shade of yellow, the drink was described by taste-testers as more lemony.

The same is true for products such as cigarettes: In the 1970s, sales of Lucky Strike cigarettes plummeted among women. Stumped as to why, marketers investigated and discovered that because the pack color, green, was not popular in the fashion world at that time, women were somehow rejecting it on that basis. Accordingly, some money was allegedly spread around the industry to get some designers to make green prominent in their haute couture. Bingo!…sales jumped and congressional hearings were held to investigate the bribes. Bribes or not, the fashion and cigarette color-coordination strategy is still being employed aggressively. (Check out your smoking friends’ clothing/pack color choices, or your own, if you are a smoker to gauge the results.)

Hence, if your company “Q” is not as popular as company “L”, you may want to consider repackaging it at your end—to the extent that professional ethics allow. The simplest way is to search for the one or two salient characteristics of the company that are most likely to offset the advantages of the competitor and make them prominent in your pitch.

If you try any of the aforementioned client-marketing Pepsi/Coke approaches, you may find that slightly more than 50% of your recruiter friends who did not try any of them will agree they are smart ideas…

….or tell you they make no difference.