This is One Very Weird Recruitment Poster

Imagine a U.S. Marine recruitment poster in an Iowa farm town bannered with the following slogan above the head of a steely-eyed, ramrod, granite-jawed pilot posing proudly beside his gleaming F/A-18 Hornet: “アメリカの誇り”.

That’s as difficult to imagine as getting through U.S. Navy Seal training if you can’t swim.

In the first place, virtually no one could read it; and those who could wouldn’t get it: “Huh? ‘AMERICAN PRIDE’ in Japanese?! Seriously?” (That’s what the Japanese, “America no hokori”, says in my imagined ad.)

It’s not just the extreme peculiarity of translating a patriotic message into Japanese. “AMERICAN PRIDE” would be weird in any other truly foreign language, e.g., German—”AMERIKANISCHER STOLTZ” (weird even in this century, not to mention the last one.)

When the pride is in the nation as well as in its own language—in both senses of “in”, there is no such problem: One of the first and few sentences among the other useless ones I think I remember from my one college course in German was “Die Deutschen sind stolz auf ihre Wissenschaft des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts“—”The German people are proud of their 20th-century science.” (Try it as an icebreaker at Oktoberfest.)

A Japanese Soldier’s Take on the Marketing of “JAPAN PRIDE”

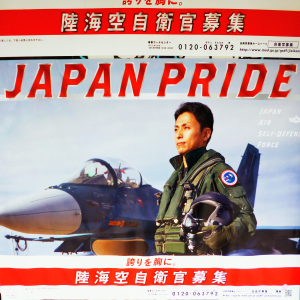

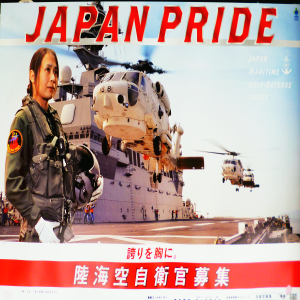

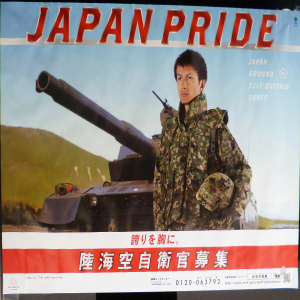

The poster shown above is not a fake; it’s the real deal: a Japan Self-Defense Force (Jieitai) production—and I know, because I photographed it this May (2014) while standing outside the small Tsuwano, Japan shop window on which it was posted, along with the other two shown here.

Now, scenic Tsuwano, population 9,000 or so, and just about the most peaceful, friendly, charming small town I’ve seen in the whole world, is a very unlikely venue for military recruitment, if only because there are so few young people living there.

But that fact aside, those posters would seem weird posted anywhere—inside or outside Japan (although apparently not weird to whoever designed and approved them).

If you think those odd posters were a PR fluke, watch this Japan Self-Defense Force recruitment video : The same message—”JAPAN PRIDE”—in florid, banner English.

Yes, I know that anything in or plastered with English in Japan is “kakkoii!”—–”cool” in Japan, but these posters left all Japanese I asked about them cold and confused. Except for one: the shop owner who posted it. Why?

The explanation is that it filled two important marketing niches that matter to him: the marketing of comics and the marketing of military careers through the coolness of English, because, as a retired Japanese army officer he has a vested interest in both.

As for his military career, it was as peaceful as Tsuwano: He was the director of the military band in which he also played the trombone.

Once his explained it, his commitment made sense, but more sense than the poster slogan itself. It still seems that English chic isn’t a sufficient offset to the unpatriotic image and impression of “JAPAN PRIDE”–a sentiment that all the Japanese I asked shared.

However, in defense of the Japan Self-Defense Force slogan, he, like other Japanese I asked, explained that patriotism among young Japanese is a fuzzy, feeble thing, and that, unlike their grandparents, they are not easily stirred to it.

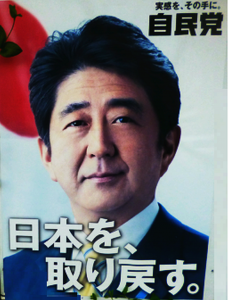

Hence, to snag them as recruits, you have to speak their language—their generational language, which, as a hook, is more likely to be English than the fervent patriotic mother-tongue rhetoric of other posters, such as that of the ruling Jiminto (Liberal) party voter recruitment poster shown here that says, “Nihon wo torimodosu!” —”Take back Japan!” (which the Japanese I asked said blends allusions to reviving the economy, restoring some Japanese cultural and military traditions—including family values, constitutional issues and addressing the ongoing Senkkaku/Diaoyu island territorial dispute with China).

Why English?

As for the fascination with English, which goes far beyond the practical necessities and convenience of English as an international business tool and cross-cultural lubricant, there are, I believe, a number of historical and psychological reasons for the craze that has never ended (even if it’s now a little less crazed than before, e.g., the once ubiquitous English “conversation lounges” have pretty much vanished as a phenomenon).

Some of the same fascination-factors also figure into the following conjectures I want to offer about why the JSDF decided to use an English-language pitch to recruit Japan’s defenders:

*Muting the Military Message:Not the likeliest explanation, this one is perhaps the subtlest—English recruitment slogans may mute any hint of Japanese ultra-nationalist remilitarization by giving recruitment an internationalized, world community-focused image (given that English is the premiere international language).

To the extent that there is any concern in Japan or elsewhere about reversion to imperial military missions and values, embedding English in recruitment ads can address these (and camouflage them, if those concerns have any validity).

Such concerns may be fueled by the implications of the current “Take back Japan!” campaign slogan of the ruling Jiminto (Liberal) party, which, as mentioned above, resonates with multiple pondered policy objectives.

The current widespread and conspicuous use of cute, indeed childish, Japanese “anime” cartoon figures in military recruitment promotions, e.g., posters and videos, can have the same effect and serve the same purpose, while pitching the recruitment at a level and in an idiom that young potential recruits are likely to respond to, much as U.S. Navy “SEE THE WORLD!” recruiting messages historically have.

The youth-oriented slogan of the anime recruitment ad shown here is the close equivalent of the U.S. slogan “Become all that you can be!” (“Jibun ga suki ni naru!”— “Become what you like!”), attesting the priority given to generational appeal in Japanese as well as in U.S. military recruitment.

*Dominance mimic: When kids and subculture wannabe’s mimic the style, speech, attire, behavior and values of their latest or lifelong idols and heroes, some of what is driving that is a kind of fraud—trading on the status of the hero by resemblance, in order to impress others, without any requirement of comparable achievement, talents, skills, etc.

The term “dominance mimic” designates, among other things, anything used to create the false impression of being the copied dominant animal or human or, more generally, as Desmond Morris, author of endlessly reprinted The Naked Ape and The Human Zoo put it, “A dominance mimic is an outward sign of the level of dominance you would like to attain, but have not.”

In the animal kingdom, harmless flies and snakes accomplish the same thing by displaying coloration patterns virtually identical with those of other dangerous, e.g., poisonous or stinging, species. It’s also the same for bikers anywhere they are tricked out in Nazi regalia.

Merely buying, rather than earning a “101st Airborne” tattoo is one example; copying Justin Bieber’s latest hairstyle (in addition to his tattoos) is another. In Japan, American-flag T-shirts do double duty: allow personal identification with America the victor and social dominance through misidentification by others, with the effect of making a Japanese guy look “kakkoii”.

Ditto for the “JAPAN PRIDE” English slogan.

*Identification with the powerful: This is behavioral and motivational psychology 101. For some unfathomable reason, humans are inclined to think that if they look and act like really powerful people or things that they themselves are not, or have access to them, they too will be (seen as) powerful.

Hence, the predictable adult and literally infantile male preoccupation with the likes of Hercules, the Rock, Superman, Batman, Men in Black, Corvettes, AK-47s, etc. (Women have Cat Woman, Wonder Woman, Oprah, etc.)

Formerly the undisputed occupant of the pinnacle of global power (by any measure) the U.S. remains Japan’s totemic G.I. Joe doll and role model and embodiment of this kind of power-identification.

*Psychoanalytic “identification with the aggressor”:A concept formulated by Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud, this has been cited as an explanation of why some inmates in prisons or captives in WW II concentration camps are known to have eventually behaved like their guards and captors, e.g., in bossing or terrorizing their peers.

It also explains why schoolyard children will pretend they are animals that terrify them and in turn terrify their playmates while in that role (unless a SWAT team is called to them away).

The general idea is that when we are subjected to the extreme stress of total powerlessness because of total control or intimidation by someone or something more powerful, one psychological defense mechanism some of us will employ is to identify with that which has terrified us and otherwise would.

This also may illuminate, but not totally account for the paradox of why some women who fear or hate men mimic them in their masculine attire, close-cropped hair, speech, social habits and partner preferences.

What such considerations suggest is that in some such cases, “know thy enemy” may be taken to the ultimate level, through the firsthand experience of becoming it.

As the defeated foe in WW II, the Japanese had reasonable incentives to identify to some extent with an ascendant America and its language. In particular, identifying with the victor, as discussed below, can salve some of the sting of defeat.

*Identification with the victor: Of course, defeat is always hard to accept. One thing that makes it even harder is having to contemplate the possibility that losing was due to one’s extraordinary inferiority, rather than to the victor’s extraordinary superiority.

Now, although these may seem to be indistinguishable, in fact they are different. The latter possibility—loss to an outstandingly superior adversary—is, as worded, consistent with one’s own excellence and conquest by a truly worthy foe. The former—loss because of humiliating inferiority compounds the pain of defeat.

On close inspection, the slogan and the history of Japan-U.S. relations suggest that the Japanese have opted for the “extraordinary victor” interpretation, thereby saving face and legitimizing identification with the victor, rather than opting for self-disavowal and profound loss of face.

The use of English in military recruitment may be a manifestation of that mindset.

*Identification with a partner(ship): Evolving resemblances between spouses or pets and their owners are often noted—partnerships in which identities become blurred over time.

In the case of pets, the animal chosen frequently serves as a personal “totem” or a so-called “transitional object”, i.e., a surrogate self, like a child’s teddy bear, that serves as a companion, stand-in, social buffer, emotional proxy or trial balloon for one’s own evolving persona—especially a persona that is, as young children’s personas are, immature and shaky.

Human partnerships can display similar characteristics—e.g., a spouse with whom one identifies in terms of success, strength, etc., and therefore psychologically identifies with, even in the absence of visibly evident similarities.

The recruiting posters may be tapping into that kind of identification: identification with a partner(ship). That would not be at all surprising, given the enduring, positive post-WW II partnership between Japan and the United States—particularly strong in virtue of the comparatively benevolent and protective dimensions of American policies in and regarding Japan.

One commonplace analogous example closer at home is that of the diehard Cubs or hardcore Canucks fan who sees his relationship with the team franchise as a “partnership” and fervently identifies with it, e.g., with team jerseys, face paint, hand-held placards, car aerial flags and team-logo emblazoned beer mugs.

Applications

Perhaps the foregoing explanations make the “JAPAN PRIDE” ads seem less puzzling and peculiar. They may even suggest fresh approaches for military recruitment efforts in other countries.

For example, given the close partnership between the U.S. and bilingual Canada, it may be worthwhile to consider a foreign-language ad that pitches a Canadian theme for the U.S. Army, say, “An Army of One, Eh? ”

Who knows? It might entice U.S. resident Canadian bad boy Justin Bieber to sign up and get shipped somewhere (else).

__________________

Note: This is another in a series of articles by Michael written while “on the road” in Japan and Taiwan in 2014.