5 Habits That Are Killing Your Career

You aren’t stalling out in your career because you lack skills. Rather, it’s more likely that bad behavior is to blame.

A recent survey from training company VitalSmarts found that 97 percent of employees have some career-limiting habit that hinders their progression at work. VitalSmarts approached 973 managers to ask them which habits were most derailing their direct reports’ careers. The managers pointed to five above all others:

- Disorganized and Unreliable:Doesn’t spend necessary time planning, organizing, communicating, and coordinating with others; fails to follow through on commitments; difficult to rely upon.

- Too Little, Too Late: Procrastinates; misses deadlines; cuts corners rather than going the extra mile to produce great quality.

- It’s Not My Job: Deflects blame; doesn’t take responsibility; clings to their job description; unwilling to sacrifice personal interests for a larger goal.

- Unwilling to Change: Is stuck in the past; complains about the future; repeats the same mistakes; expects others to accept them as they are; drags feet in taking on new approaches.

- Cynicism: Is often the contrarian; finds fault before looking for benefits; is overly critical.

The Performance Review Disconnect

Despite the fact that managers have identified these five habits as career-killers, employees are by and large unaware of their bad behavior. In part, that’s the result of a disconnect between managers and employees during performance reviews.

As VitalSmarts Vice President of Research David Maxfield explains, “When we asked people who had come out of performance reviews what their boss wanted them to do differently and what they learned from the performance review, they overwhelmingly said that, to the extent their boss had any dissatisfaction at all, the solution was to take a course or skill-up in some sort of technical area. But when we talked to the managers, it wasn’t about skill-building at all. It was about behavioral problems – very different from the message that their direct reports heard.”

Perhaps employees are walking away with such skewed messages because managers aren’t very optimistic about the situation. According to VitalSmarts, bosses report only 10-20 percent of their employees can actually make the lasting changes needed to kick these career-limiting habits.

While Maxfield acknowledges that changing your habits is harder than learning new skills, he doesn’t believe it can’t be done.

“It’s not that people can’t change, it’s that very few people do change,” he says.

Fans of long-running radio variety showA Prairie Home Companion will be familiar with creator Garrison Keillor’s description of the fictional town Lake Wobegon as a place where “all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.”

The “Lake Wobegon Effect,” which takes its name from that last bit about all the children being “above average,” refers to the fact that almost all of us believe ourselves to be above average – a statistical impossibility.

Maxfield describes a survey in which people were asked, “Are you above average?” and 80 percent of respondents answered in the affirmative. The Lake Wobegon effect, Maxfield believes, is one of the reasons why so few people are able to permanently change their behavior.

“One of my colleagues says the problem is biology: Our eyes point the wrong direction,” Maxfield says. “We’re not looking at ourselves, we’re looking out at the world. We don’t see our own inadequacies.”

To make matters worse, people are often reluctant to point our inadequacies out to us. Even our bosses aren’t so good at it – recall the performance review disconnect explored above.

The other problem preventing us from changing, Maxfield says, is that when someone does point out a behavioral problem, many of us go into denial. In the VitalSmarts survey about career-limiting habits, 80 percent of employees blamed the problem on their bosses, not on themselves.

“If you’re unwilling to own it, then the chances you are going to change are pretty small,” Maxfield says.

Maxfield has some ideas about how people can kick their career-killing habits, but he stresses that “before anyone can adopt these tips, the first step is to accept it is your problem.”

Accepting a behavior as your problem isn’t simply a matter of being told you have a bad habit you need to address. It means consciously choosing to address the problem after careful consideration.

“What people forget sometimes is that you need to ask yourself, ‘Is this a behavior I am willing to change, or would I rather find a new boss, find a new job, and live with the status quo?'” Maxfield says.

Bad Behavior Is a Team Sport

If, on the other hand, you’ve decided making the change is worth it, the first thing to recognize is that willpower alone won’t fix a thing.

“Often, when you have a bad habit, it’s almost always a team sport – you have accomplices who are encouraging your bad habit,” Maxfield says. “You have to take some accomplices and bring them over to your side.”

For example, say you’re one of the “disorganized and unreliable” ones. Your habits didn’t start out as bad ones. As Maxfield says, your habits likely developed as “the best way of coping with the world as [you] found it.”

“Say you’re a new employee, and you’re getting along just fine,” Maxfield elaborates. “Maybe your peers would not describe you as disorganized and unreliable, but you don’t really use a calendar very effectively or plan your workday very effectively, but you don’t have to – you have the weekend to catch up, and your job is not all that responsible anyway.

Over the years, a few things change. You get promoted and gain a lot of responsibility. You settle down, get married, have some children – all of which adds even more responsibility to your life. Now you don’t have the weekend to catch up anymore. Your disorganization is becoming a significant hindrance to your professional success.

“The mistake we tend to make is thinking, ‘Well, if I have enough willpower, I can overcome anything,'” Maxfield says. “But I forget that my family is lined up against me spending more time at the office. They don’t think this a bad habit, though. Your family would like to see you spend less time at the office.”

Often, when a person is stuck in a bad habit or situation, it’s not one thing keeping them stuck there. Instead, multiple factors are at work, Maxfield says. That’s why he and VitalSmarts have come up with a sort of “typology” that allows people to discover the influences keeping them stuck.

“We’re like the fish that discovers water last: Swimming in a sea of influence, and we don’t even notice it,” Maxfield says.

Become a ‘Scientist’ to Kick Your Career-Limiting Habits

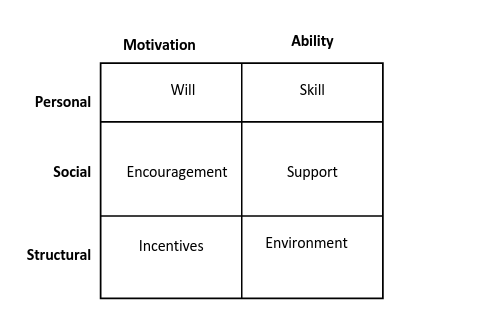

That typology of bad influences developed by Maxfield and co. looks like this:

Using this chart, people can pinpoint where their negative influences are coming from and what to do about them.

Returning to our disorganized and unreliable example, perhaps you pinpoint one of your bad influences in the social ability, or “support,” section: Your family doesn’t want you spending more time at the office so you can stay ahead on your work. They’d rather spend time with you.

Of course, we’re using the phrase “bad influence” rather loosely here. Your family isn’t wrong to want to spend time with you, and you aren’t a bad person for prioritizing family dinner over constant late nights in the office. So, assuming you have accepted that disorganization and unreliability is your problem and is worth fixing, your next step is to “become almost like a scientist,” Maxfield says. You have to dig deeper to the underlying causes of your behavior and find solutions that work for you.

“The subject we’re studying is ourselves,” Maxfield says. “Can we define the behaviors that are a problem and then track down those times, places, and circumstances where it becomes a problem?”

If you’re disorganized and unreliable, maybe you discover that one of your big problems is saying “no” to people, which means you often end up with more work than you can realistically handle. Now that you can’t use the weekends to catch up because you want to spend time with your family, you have to find a better solution – which you can do by looking at each box in the typology and taking some corresponding actions. There are numerous ways to improve your will or incentivize yourself, for example, but here are six to get you started:

1. Personal Motivation (Will): Create a Personal Motivation Statement

A personal motivation statement can help you solve the conflicts that often arise between short- and long-term goals.

“We have our long-term goals that we’re after, like a career advancement goal, and our spouse buys into it, our family buys into it, we all buy into it,” Maxfield says. “But in the short term – on a Friday night, when you have tickets to the theater but you have a deadline that will require you to stay late and miss the theater – your motivation is not to get that career advancement, it’s to go to the theater with your spouse.”

In such situations, you can use personal motivation statements to remind yourself in the short term of the long-term goals you may be abandoning to pursue immediate satisfaction.

2. Personal Ability (Skill): Get Some Training

You could always use a new set of skills, no matter what your situation is. If you’re disorganized and unreliable, perhaps you can learn some time-management and calendaring skills to help you get more done on time.

Just remember that truly building skills requires not only education, but also active training.

3. Social Motivation (Encouragement): Hang With the Hard Workers

Rather than spending your time with slackers, Maxfield suggests “find[ing] accomplices who have the same goals as you have and model off of them. Do what they do.”

4. Social Ability (Support): Find a Mentor

Your mentor should be someone you trust and who cares about you. It should be someone with whom you can be honest and who can be honest with you. Your mentor needs to be able to tell you the hard truths, or else you’ll just end up in denial like most other people.

5. Structural Motivation (Incentives): Put Some Skin in the Game

Maxfield tells the story of his neighbor in Park City, Utah, who spent time on the Olympic Nordic combined team. When this neighbor was tasked by his coach with losing ten pounds, he put a stack of $20 bills on his mantel, above the fireplace.

“He tells his wife, ‘Every Friday, I want you to give me the hard truth. Did I stick to my diet and my training? If I didn’t, we’re going to burn a $20 dollar,” Maxfield recounts. “So he had some skin in the game – and he said he never burned a bill!”

6. Structural Ability (Environment): Control Your Environment

Take control of your workspace and the environment around your workspace. Make it into a space that is, for you, conducive to work.

“It may be creating a quiet workspace at home, or it might be removing things like electronic disruptions, or it might be purchasing some apps that could help with organization,” Maxfield explains.