Dying for a Chance to Get a Cheat’s Job

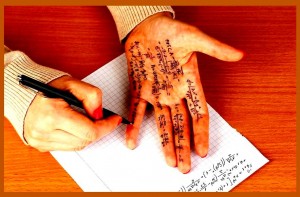

Dying to defend a claimed right to cheat seems to fall into the category of fatal defense of seemingly unprincipled behavior—and that’s precisely what has happened to some students in Bangladesh during periodic riots in defense of a claimed right to cheat on their university entrance exams.

Cheating and Dying to Get a Cheat’s Job

Many other rioters have cheated, surreptitiously and implicitly claiming that right to cheat, with less dire consequences—but for similar purposes: to “succeed” and, as recent research in India suggests, with a bias toward succeeding in getting and keeping a government job, presumably or preferably perfect for a cheat.

While students elsewhere can survive getting drunk, torching and overturning police cars when their hockey team wins or loses, those Bangladeshi student demands and riots for a “right to cheat” got some of them killed by besieged or deployed police.

It’s true. I was there when on an occasion when it happened and read about the details while in Dhaka, capital of Bangladesh, on my way to India, back in the 1980s, during the post-coup rule of strongman General H.M. Ershad, about whom almost all other stories in that paper seemed and probably had to be. Even more shocking is the fact that this wasn’t the last time a right-to-cheat riot to cheat eventuated in death in Bangladesh.

The same surreal scenario played out again in Bangladesh in 1990, when one 18-year-old student was killed by police when angry crowds demanding the right to cheat attempted to storm an exam center.

Government Career Cheaters

Why they were, at that times, so passionate in their defense of cheating is a story in itself, to be explored shortly, below. But, fast-forward to today—and to one contemporary reason for cheating implied by a recent scientific study conducted in Bangalore, which discovered a correlation between apparent cheating and interest in having a government job.

The study found correlations between interest in having a government job and cheating in the form of almost certainly falsified student self-reports of high scores [that won corresponding cash payoffs] in a controlled experiment with rolled dice.

Those whose improbably high dice totals—i.e., abnormally high reported numbers of “5”s and “6”s in 42 rolls—could not be attributed to chance were found to have a statistically significant 6.3% greater likelihood of expressing an interest in having a government job. That means a jump from 1 in 100 among non-cheaters to more than 6 in 100 among the presumptive cheats.

[Presumably this would be a government job to be sought by duping, through cheating, first, a university and then a government recruiter or employer—unless the goal is to hire liars and cheats.]

A key inference from the study is that where government or business corruption is pervasive and recognized, even if not broadly accepted, it is likely to become permanent in virtue of magnetically attracting cheats and other scoundrels, while repelling the more virtuous.

In turn, this raises interesting questions about how to reform hiring practices that attract the wrong types, given the will and recognition of the need to do so. It also invites considering tools that can be devised to effectively screen against cheats—apart from standard procedures such as checking references, confirming claimed degrees and the like.

Make no mistake, student cheating is an early-stage Oliver Twist street urchin’s precursor to, if not prerequisite of, subsequent adult professional corruption.

The Cheating-Corruption Nexus

As a form of fraud, successful cheating offers practice in law-and-rule-breaking; seeking or offering unfair advantage; exploitation of unauthorized access to information, resources and power for gain; betrayal of trust; rationalization of specious self-entitlement; refining arts of deception; “winning” at any cost; and family-first machinations—“I did it to make my parents proud”, “I can’t get a good job to support my little brother, if I don’t cheat”, etc.

When cheating is the seed; corruption is the fruit. Alternatively, you can think of corruption as form of rule-breaking cheating through fraud, favoritism or force.

In practice, however, professional corruption is broader in scope than exam cheating, since corruption utilizes coercion through threats and intimidation, as well as a cheater’s bribery, deception and fraud.

Moreover, favoritism, e.g., nepotism, plays a much larger role in adult governmental and business corruption than in student exam scenarios, despite the iconic “teacher’s pet” manipulation of a teacher into providing unfair exam tips, “previews” or even, in the extreme, exam questions and/or answers.

The “riot to cheat” demonstrates a fact about all presumed unethical behavior: Those who are behaving in ways deemed unethical not only rarely believe they are really doing anything they consider wrong; they also believe they have right and rights on their side and will riot or worse, if necessary, to make that clear.

From that self-serving “ethical” perspective, cheating and corruption are rationalized not only as rights, but-—in the extreme—probably also as duties.

A “Right to Cheat”—Huh?

But how on Earth can they imagine there can or should be a right to cheat? The answer is pretty consistent—and not only in Bangladesh. A non-lethal right-to-cheat riot in China’s Hubei province in 2013 was justified by an angry mob of 2,000 on the grounds that it is “unfair” to disallow cheating, when so many already are getting away with it.

As their verbatim chant and the protesters in Bangladesh equivalently put it, “We want fairness. There is no fairness, if you do not let us cheat!”

That Chinese mob mantra, echoing that of students, parents and mobs in Bangladesh, was predicated on the claim that the right to cheat is necessary to level the university admissions and employment playing field dominated by the rich.

The argument was that the wealthy, unlike everybody else, can well afford teacher bribes, sneaky technology and other cheating-facilitating resources, such as hired operatives paid to dangle answers from windows above the exam room window [yes, that’s been done].

Even in Honest Japan

Perhaps that’s what motivated the mass cheating I exposed during a final exam for one of my courses at a posh Japanese women’s college I taught at in Kobe in that era.

What made that cheating especially shocking was that such behavior seemed strikingly at odds with strong Japanese cultural norms of honesty that pretty much guaranteed that if you lost your wallet, somebody would turn it in—along with all of your cash, credit cards and its other contents.

Despite my repeatedly reminding my 100 students that cheating would not only be inappropriate, but also unnecessary—because it was an open-book exam based on questions handed out a week in advance, I detected—first one, then another and another—suspicious use of a finger as a bookmark in the closed books brought to the exam.

Lo and behold, forbidden pre-written answers were pasted into those pages. Just as the scale of the cheating became clear, the end bell rang, prompting the culprits and everyone else to scatter and flee before I could react.

Apparently following mob logic, the department did nothing—on the grounds that it would be unfair to punish only those who got caught.

Following that logic of “fairness” down the road cheaters take to a career in Bangladesh and China, it would not surprise me to read a report about an enraged mob somewhere, sometime shouting a corresponding job-chant:

“It’s unfair to hire only those who get hired.”