Learning to Thrive in a Global Talent Shortage

Globally, 36 percent of employers reported difficulty filling jobs, a seven-year high. Of the employers who said they were facing a talent shortage, 54 percent said the shortage has a “medium or high impact on their ability to meet client needs.”

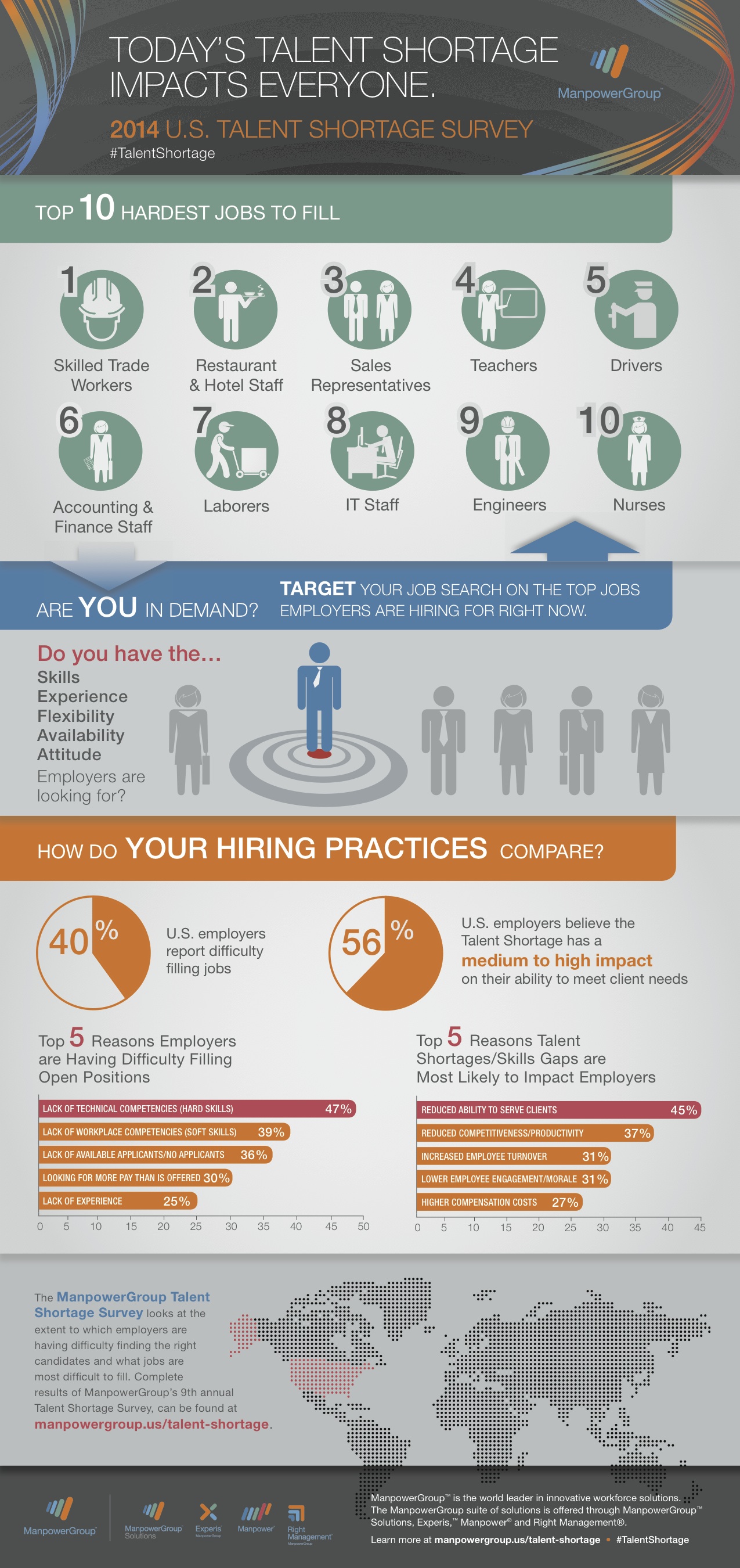

Shifting focus to the domestic situation, the ManpowerGroup found that 40 percent of U.S. employers were having difficulty filling jobs — not an all-time high, but up one percent from last year; 56 percent of U.S. employers believe the talent shortage has a “medium to hight impact on their ability to meet client needs.”

The ManpowerGroup also produced lists of the roles that employers are having the hardest time filling. Globally, these are, in order:

- Skilled trade workers

- Engineers

- Technicians

- Sales representatives

- Accounting and finance staff

- Management/executives

- Sales managers

- IT staff

- Office support staff

- Drivers

The U.S.’s “Top 10 Hardest Jobs to Fill” list shows some overlap with the global list, but it is quite different overall. Again, in order:

- Skilled trade workers

- Restaurant and hotel staff

- Sales representatives

- Teachers

- Drivers

- Accounting and finance staff

- Laborers

- IT staff

- Engineers

- Nurses

For help making sense of the survey — what is the talent shortage? Why are we facing it? What can we do about it? — I turned to James F. McCoy, ManpowerGroup’s Vice President of Recruitment Process Outsourcing (RPO) Practice.

The Talent Shortage and the Skills Gap

According to McCoy, we should understand the talent shortage and the skills gap as “part and parcel of the same issue.” The “talent shortage” is the name we give to the state of affairs in which employers have a demand for talent — i.e., have certain roles they need to fill — but lack the qualified applicants to fill those roles. This situation comes about because of the skills gap: the candidates available for these roles do not have the necessary skills to perform them.

For evidence of the relationship between the talent shortage and the skills gap, McCoy points to the positions on the “Top 10 Hardest Jobs to Fill” lists. “If you look at the roles, they are primarily roles that require some sort of training or specific certification,” he says. “A lot of the challenge of the skills gap is that universities, high schools, and even primary education are not preparing the talent. There’s a mismatch between what they’re graduating versus what employers require.”

McCoy points to drivers as an example of the mismatch between employer demand and employee supply. Drivers made both the global and U.S. “Hardest Jobs to Fill” lists, coming in at spots 10 and 5, respectively.

“You would think that drivers would be a fairly easy role to fill,” McCoy says. In fact, a lot of people are worried about running out of commercially licensed drivers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average age of the U.S. commercial driver is 55. At that rate, the profession is headed towards extinction.

But despite the massive demand for drivers, companies are struggling to fill their open positions. They simply can’t find the qualified talent to do so. “Most transport firms would add more trucks to the road if they had the opportunity to do so,” McCoy says. “They just simply can’t because they can’t hire drivers fast enough.”

The driver shortage is partially a matter of mobility, McCoy says: you need to have a certain kind of mobility to be a commercial driver, and not everyone has that freedom. But another reason — one that drives talent shortages across all sorts of industries — is education. Companies can’t find drivers because so few people are training to be become drivers.

“Certainly, [driving] would be a micro-example,” McCoy says, “but other examples, like skilled trade workers, where you may need many years as an intern or apprentice to be able to become licensed, or engineers, or accounting, or finance: all of these require very specialized education that the universities aren’t catching up with, and they therefore haven’t caught up with the demand that employers have.”

Addressing the Talent Shortage

Because education is a major factor in the skills gap, it’s one of the areas where we can begin to address talent shortages.

For example, nurses — though still somewhat difficult to find in the U.S. — used to be even scarcer. As a result of the demand for nurses, “schools opened up many more positions in nursing programs,” McCoy says. “Many more people looked at nursing as a profession and started to study nursing. All of a sudden, you started to see nursing drop on the list of talent shortages.”

But educational institutions cannot, in and of themselves, solve the shortages. For one thing, job seekers need to pay attention to employer demands. “I don’t think a lot of job seekers are aware of [the shortages],” says McCoy. “I think job seekers might have slightly different educational priorities if they were to take a look at where you see talent shortages.”

If we turn again to the nursing example, we’ll see that decisions to open up more space in nursing programs were not enough on their own — students needed to take advantage of the opened spaces and choose nursing. They needed to be aware of what was going on in the workforce and recognize that nursing was a plausible option.

“Because schools were aggressive, and because candidates said, ‘Okay, this is a viable career path for me’ … then we started to see the gap close between the employer need and the employee availability,” McCoy says.

We may also want to look toward strategic public-private partnerships in helping to alleviate talent shortages. “An example is: the U.S. is one country where immigration has filled a key need for certain skill sets. But other countries have much more rigid immigration policies that don’t allow that as an outlet,” McCoy explains. “So you can have a terrific education system, but if you simply don’t have enough people coming into the market to do the work, you’ll still suffer from the same skills gap and talent shortage nonetheless.”

Japan is a good example of what can happen to countries when their immigration policies are too rigid: of all the countries surveyed by ManpowerGroup, Japan reported having the most difficulty in filling jobs, with 81 percent of employers reporting that they faced a talent shortage. That’s more than double the global average.

Reconsidering Work

Employers may be the victims of the talent shortage, but they don’t have to be passive about it. They, too, can help combat the shortage by “reconsidering their work,” says McCoy.

“We’re seeing a way of looking at work not just as an employee filling a job, but how you actually get the work done. How can we attract the best employee to do that?” McCoy explains.

Reconsidering work means taking new, outside-the-box approaches to finding talent and filling jobs. “It’s coming up with creative solutions, like looking around the world [for talent], to where work is delivered, to even restructuring the jobs so you can attract a demographic that you might not have been able to attract in the past,” McCoy says.

Offshoring is a good example of how some companies are reconsidering their work, says McCoy: “Some offshoring has been driven by cost pressure, but in reality what we’re seeing more and more is that offshoring a lot of times is driven frankly by where talent is available.”

Similarly, McCoy says organizations should look into making capital investments to “reduce the reliance on some of these key skill shortages.” This could mean investing in new accounting systems when financial talent is tight, or it could mean finding new ways to support your office when support staff is hard to come by.

Remember: the Shortage is Global

No matter what strategies job seekers or employers adopt to deal with the talent shortage, we’d all do well to remember that, in our contemporary economy, this truly is a globalissue. The talent shortage cannot be dealt with in isolation.

As an example, McCoy returns to drivers. “People are often shocked drivers are on [the list]. Well, different demographics are driving that — no pun intended,” he says. “One of the things that’s creating huge demand in the U.S. is the increase in the fracking industry. You look at places like western Pennsylvania, North Dakota, west Texas — they are literally pulling in drivers from surrounding states, from two or three states away. So what happens is, a demand for drivers in western Pennsylvania is now creating a shortage of drivers in Massachusetts.”

“It really speaks to the fact that we’re in an interconnected world,” McCoy says. “A talent shortage in one area puts pressure directly on surrounding states, surrounding communities, surrounding countries, for that matter.”

ManpowerGroup’s 2014 Talent Shortage Survey, U.S. Results

For global results, click here.