Limiting Supermarket Freedom of Expression

—Reflections on 1st-amendment claims and risks of employers, employees, clients and customers

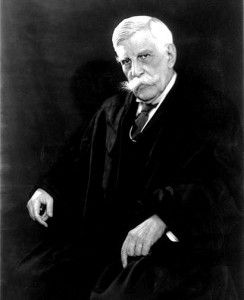

“The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”—Associate Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., 1919

In the private sector, depending upon the regional and global jurisdiction or business sector, and unlike what prevails in government employment, e.g., in the U.S., workplace free speech is severely circumscribed and often basically unrecognized and unprotected.

To the extent that the law or an employer recognizes any right of self-expression in a workplace—including in the form of wearing a “Capitalism Sucks!” T-shirt—such a right is usually balanced by a corresponding employee obligation to refrain from obscene, defamatory, harassing, discriminatory, endangering (e.g., spike-studded tunics) and other problematic self-expressive content and methods.

Moreover, an employee should not expect her claim to a right to solicit, disseminate, otherwise impart or receive information at work to be recognized by an employer or a court.

However, employer, employee, customer and client attitudes, like laws, evolve—especially under the pressure or inspiration of resistance to them, which initially takes the form of at least thinking about them. Recall Rosa Parks fateful December 1, 1955 decision to express her claim to the right to keep her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus when the white bus driver ordered her to vacate it for a white woman. One brave step for a small woman, one gigantic leap for the thinking of mankind.

With her example in mind, and because they involve customers and employer, as well as employees, the supermarket scenarios that follow are designed to stimulate and encourage that kind of thinking.

The Deadly Dog

A supermarket-chain vegan cashier truthfully tells a customer at checkout that the bacon, sausage and hot dogs she’s buying, like most packaged and processed meats, contain the cancer-causing preservatives and antimicrobial agents sodium nitrate and/or sodium nitrite, linked to a variety of deadly cancers. The customer leaves the meat at the counter and departs with her other, now fewer purchases.

Uh-oh, the cashier is in trouble with the manager, who, having overheard her comments is going to do something about it. But should he?

In this and comparable scenarios, if we want to be sure we are supporting the right side when it comes to workplace rights , the immediate reflex to automatically morally, emotionally or legally side with management (or with the employee) needs to be resisted and tempered by some very careful reflection on assumed principles, scenarios and case details, in the form of the kinds of analyses that follow, below.

A Manager vs. Employee Free Speech Conflict

If the cashier had lied to the customer, that lie as “free speech” would not deserve protection from the manager’s wrath. However, even though the cashier’s behavior is more like truthfully shouting “Fire!” in a crowded theatre, the franchise owner and manager, overhearing the remark, may be gripped by an irresistible desire to exercise what he takes to be his own right of private and corporate free speech by sending a written negative performance report to the head office as part of the employee’s permanent record, by pushing for dismissal of the employee, or by doing both as punishment for the employee’s hurting the store’s bottom line and being “unprofessional”.

From the cashier’s perspective, that would be absurd and ironic: The employee’s telling potentially life-saving truths needs to be punished, even when the company may in fact benefit from it?

How could the company benefit from a lost purchase? Here’s how: In taking any of those punitive steps, the manager will overlook the possibility that, impressed with the honesty and integrity of the cashier, the newly-enlightened customer may appreciate that candor and health information as a shopping bonus and, deciding to become a loyal customer, ask the cashier for recommendations upon entering the store next time.

But there may be other reasons for not punishing the outspoken employee: Indulging his urge to punish the cashier can conceivably create a legally tricky situation for the manager. If he sends the negative employee report and if it can be demonstrated that it wrongfully damages the cashier’s (re)employment prospects, the question arises as to whether the report can or should be treated as “protected speech” or as litigable defamation in the form of libel or a case of what are called “false lights” damages. (Not to be confused with the harm caused by false fire alarms, “false lights” damages comprise mental or emotional damage to the plaintiff, rather than to his reputation and economic bottom line, which is what would be required for a defamation suit).

Nonetheless, the manager may imagine the law is on his side: If the supermarket manager is familiar with Associate Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and his 1919 Schenk v. United States “clear and present danger” test of free speech, viz., whether what is said, like falsely shouting “Fire!”, presents such a clear and present danger, the manager may think he is acting within the scope of his own free-speech rights to deny that the employee has any such right to endanger sales in an analogous way.

Here’s why: Although not part of Justice Holmes 1919 argumentation, theoretically it can be argued that truthfully shouting “Fire!” may or should be punishable in some circumstances, because of what legal experts call “TPM” —“Time, Place and Manner”—considerations often invoked as factors that can undercut a claim to protected speech.

Despite allowing that the cashier was telling not only what she believed to be the truth, but also what actually is the truth, the manager could still try to argue that the employee chose the wrong TPM and thereby created a “clear and present danger” to store sales and the company. It was the wrong time—during peak-traffic hours at a busy register, when replacement shopping is quite inconvenient; the wrong place—on the job; and the wrong manner—e.g., the employee should have suggested purchasing something comparable or higher in price as a replacement.

The manager may also be tempted to analogously argue that even what is ostensibly the no-brainer case of truthfully and therefore reasonably shouting “Fire!” may run afoul of the “manner” criterion, if screamed in a panic that causes a deadly stampede to the exits, instead of being calmly voiced, with helpful pointing to the doors.

The moral and legal fulcrum in weighing this issue is likely to be the question of whether in fact the employee endangered anything and failed to fulfill a duty to promote an alternative sale as an alternative manner of self- or proxy-expression (for example, on behalf of PETA).

Value Statements vs. Descriptive Statements

A second employee, stocking the baked-goods aisle, tells a customer that the sliced white bread the store sells is not as good as 100% whole wheat, an item the store does not stock. This elicits the same response from the manager, even though, like the first employee’s comment about sodium nitrite, it is not false.

However, in this latter instance and on the basis of a philosophical theory of language called “emotivism”, “X is not as good as Y” is not false, but only because it also is not strictly speaking true, probably true or even possibly true. Instead, the emotivist argues, it is a subjective, non-factual “value judgment” and emotive expression (like “white bread—boo!”) about the (de)merits of the bread. That is to say, saying that “X is not good”, “X is bad”, “X is wonderful”, or “X is not as good as Y” are mere emotionally-based cheers and jeers, rather than expressions of empirically testable, litigable cool and calm factual claims about anything, e.g., “devoid of wheat germ, natural vitamin E, natural B-complex vitamins and fiber”—said of bread.

According to the emotivist, this second employee, in virtue of not having made a claim that is literally and objectively true or false, confirmable or disconfirmable, may, like the truth-telling cashier, be able to make a strong case for her remarks’ being protected speech, much as advertisers often can by pasting purely subjective and ambiguous “Better!” labels immune to factual disproof on their packaged goods, in virtue of their ambiguity and subjectivity.

Working the same approach, an emotivist employee might try argue for the right to boo the boss at work, on the grounds that no facts are being alleged or implied (since values and facts never imply each other) and therefore no libel or defamation is being committed.

On the other hand, on some philosophical analyses of normative terms such as “good”, “bad” and “better”, such terms are not purely jeers or cheers (R.M. Hare, The Language of Morals, Oxford University Press). Rather, they do have some descriptive content, e.g., “not good bread”, widely connoting, among those who dislike it, “bread without natural vitamin E and bran”, which would then impose a burden of factual proof of the bread’s alleged shortcomings on the shelf-stocker employee. Likewise, on this analysis, employee booing of the boss could be interpreted as carrying factual connotations that may have legally justifiable adverse consequences for that employee.

A Manager vs. Customer Freedom of Expression Conflict

A lawyer pushing a supermarket shopping cart down an aisle starts to breastfeed her crying infant. The manager asks her to leave, even though she claims a right to express her maternal instinct, as a direct and equivalent expression of her love for her child and a symbolic expression of support for individual and civil rights, irrespective of whether a venue is public or private, on the grounds that civil rights (e.g., enforced through racial desegregation of U.S. and South African restaurants) trump property rights.

Notice that although “freedom of expression” and “freedom of symbolic expression” are concepts broader than “freedom of speech”, they are, within the public arena of governance generally equally, if not more, fundamental and sacrosanct, to the extent they are recognized at all. For example, kneeling in prayer in a park or having a Mohawk haircut, while not speech, are protected forms of public self-expression.

Employee vs. Citizen Freedom of Expression

Nonetheless, they are somehow not as widely acknowledged in the workplace, where genuflecting in front of a client or having a Mohawk cut can cost somebody a job, even though neither can cost one’s citizenship or right to vote.

The glib response, “Well, the Mohawk cut will hurt our brokerage”, may protect the Wall Street firm in the short and narrow term, but at the price of culturally reinforcing bottom-line biases against freedom—a sad reminder that there is no shortage of those who would, to paraphrase both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, sacrifice someone else’s freedom for their own purchases of securities.

As for a brokerage client who might demand the replacement of a Mohawk-clipped broker (in fact, as rare as a Mohegan tribesman), there is the not entirely remote possibility of a defamation or “false light” suit filed by the broker against the client.

Leave It to the Experts?

These foregoing commonplace, yet legally and morally knotty free-speech and free-expression scenarios illustrate some of the key considerations that must be given weight in any attempt to intelligently think about, propose and decide whatever limits—if any—should be imposed on expression of ideas, beliefs, other information, attitudes and emotions by employers, business owners and managers, employees, customers and clients.

Of course, there are the results-oriented pragmatic types who will argue that the pressures and practicalities of employment make such reflection on free speech and the time spent on it an ivory-tower academic’s luxury, if not an extravagance, and naive, if not trouble-making workplace idealism. Better, they say, to leave deep thinking about such deep issues to the likes of Justice Holmes, who got paid to do precisely that.

Perhaps, they are right. Maybe we should leave it to the courts, philosophers or employers to decide whether the boss has a right to shout “You’re fired!” in a crowded office.

Image: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Of course, this article isn’t meant to offer specific legal advice. Please talk to a lawyer about any serious matter.