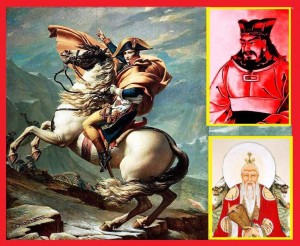

Organizational Leadership Styles: Napoleon vs. the Two Tzus

But then there’s the observation of Lao Tzu (“Lao Zi”—“??”, in modern Chinese) in his Taoist guide, the Tao De Jing (“Way”+ “Virtue” + “Classical Text”): “A leader is best when people barely know he exists; when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say, ‘We did it ourselves.’”

This is echoed in the thoughts of the second Tzu—Sun Tzu (also, “Sun Zi”—”??”), in The Art of War: “What the ancients called a clever fighter is one who not only wins, but excels in winning with ease. Hence his victories bring him neither reputation for wisdom nor credit for courage.”

Napoleon vs. The Two Tzus

Napoleon vs. the two Tzus exemplifies two diametrically opposed ways of thinking about and exercising leadership, despite their comparable fame, historic credentials and success in application. Given the prominence of each of them, it is altogether natural to ask how they can both be right—or, more insightfully, to ask under what circumstances they are to be followed.

These considerations can be distilled into one question: Under what circumstances should a leader—battlefield or workplace—lead visibly or invisibly? In this context “visibly” is to be taken not only literally, but also organizationally, in terms of top-down inspiration, guidance and control the source of which, viz., the leader, is evident to those inspired, guided and controlled.

The “Great Man” vs. “The Gray Man”

Influenced by “Great Man”, rugged individualist and heroic images of history and entertainment, Western cultures are far likelier to favor the Napoleonic approach to leadership as a model to be followed and as a tool of historical and organizational narration and explanation.

From this Great Man perspective, failure of organizational leadership, as well as success, can also be publicly showcased prescriptively (as something to avoid) and descriptively (as an account of what happened historically, culminating in catastrophe). Cases in point: the role and style of FDR in successfully creating New Deal jobs in Depression-era America and the failure of Herbert Hoover tasked with the same job earlier.

The Art of Following

Since Lao Tzu’s thinking about the subject is likely to seem alien to anyone subscribing to the Napoleonic school of leadership, presentation of a bit more of it is in order. In theTao De Jing, he says

“The river carves out the valley by flowing beneath it.

Thereby the river is the master of the valley.

In order to master people

One must speak as their servant;

In order to lead people

One must follow them.”

On the “Great Man” historical interpretation of this advice, a great leader should, at some point, serve as a great follower, just as Napoleon the corporal did before becoming Napoleon the emperor.

That makes sense, because the corporal Napoleon could inspire other corporals not only because he was a role model for them, but also because their minds, desires and needs were once his, transparent and therefore easy for him to grasp, rely on and engage.

A poor follower may make a poor leader, since (s)he cannot walk in the boots of the former as the first key step to wearing the mantle of the latter. If you do not feel or believe in the mystique or right of leadership when you are expected to be a follower, it will be very difficult to sustain or understand it as a leader.

But Lao Tzu is not talking about climbing this kind of career ladder. His advice is more paradoxical than that: A leader leads by following, period, or by being followed without obviously leading.The modern analogue of the former is a president or party whose policies are decided by Gallup polls.

As for the stealth leader, Lao Tzu saw a great leader as being more of a “gray leader”—an éminence grise(a “gray eminence”—a colorless, but secretly powerful influence on decision makers of the kind exerted by those who preside over things).

Sun Tzu’s message is similar, but not identical to Lao Tzu’s. He allows for greater visibility, but with an appearance of effortlessness (a concept central to Lao Tzu’s Taoism) and therefore of a kind of ordinariness. A Sun Tzu and Lao Tzu CEO would have a folksy, unprepossessing manner and a seemingly unimposing hands-off leadership style—a kind of T-shirt, backstage leader.

When to Ride, When to Hide

The differences between the two styles understood, the question becomes when to use them.

- When working with staff who take pride in their originality, creativity and autonomy, the best leadership may amount to not much more than permissions. When control from the top must be exercised, it may be disguised through skillful use of suggestion—planting ideas as seeds that will appear to sprout from the minds of staff, i.e., leading their horsepower to creative waters without forcing anything or saddling up to lead the charge yourself. Lao Tzu applies here.

- When a leader’s success depends upon being a role model, e.g., in multilevel or pyramid marketing, the Napoleonic model seems the clear choice—or perhaps is simply inescapable.

Distributors or other agents at the bottom looking up, drooling and nipping at the top dog’s heels (or hooves) and success will, as a minimum, see him or her as leading by example, irrespective of whether (s)he is the boss or just a heavily promoted underling.

When the leadership is through control as well as by role-model example, it will be harder for the leader to lead invisibly.

- If the organizational structure is “flat”, i.e., minimal or no hierarchy, bottom-up control is possible, e.g., through group and democratic decision-making, which can reduce leadership to presiding over proceedings and maintaining order. No rearing Napoleonic steeds here, just the subtle maneuverings and machinations of an éminence grise.

- When leadership objectives conflict with underling objectives, leadership will, as a minimum, have to be disguised, if not altogether concealed from the rank-and-file patsies.

For example, if the real purpose of a war is to seize oil, prevent a switch to a new global petro-reserve currency, test and sell new weaponry, and to hand out lucrative reconstruction contracts to crony companies, this will have to be repackaged and disguised as “liberation” or “national security”, in this variation on Lao Tzu’s theme: “When his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say, ‘We did what?’”

Ironically, the appearance of Napoleonic leadership may serve as a tool for this kind of Lao Tzu/Sun Tzu shadowy control. The same script covers whatever globalist New World Order conspiracies that exist. Here, the thought of Sun Tzu is apt: “All men can see the tactics whereby I conquer, but what none can see is the strategy out of which victory is evolved.”

- The directionality of information flow and control does not automatically determine the more suitable model—Napoleonic or Tzu. Both styles are compatible with unidirectional top-down control. However, the Napoleonic high-visibility approach is less feasible with bottom-up flow, as argued above, unless the leader’s role is merely to follow.

- The model to follow may, in some circumstances, depend less on the organizational structure or agendas of the leadership than on the existing level of stability or crisis. The Lao Tzu model seems better suited to calm times and situations to the extent that it capitalizes on the possibility of “percolation” and soft trickle-down control, rather than forceful, visible action and take-charge command.

Martial law serves as a good example; the normally inconspicuous military becomes very visible in a crisis, as does its always operative, behind-the-scenes leadership.

A business analogue would be manifest and forceful leadership to avert a hostile takeover. Likewise, if a start-up enterprise is running out of cash, otherwise invisible leadership will have to yield to take-charge, lead-the-charge fundraising leadership.

A perfect niche for Sun Tzu’s effortless leadership is an organization in which making success look easy motivates followers and underlings. Once again citing the example of multilevel marketing, making achievement of the distributor’s or agent’s dream look easier than it actually is can be a key role for management in top leadership positions.

Horse Sense

When pondering the differences and suitability of Napoleonic and Tzu models of leadership, be mindful of the fact that whether you are a leader or among the led, having some understanding of which form of leadership is guiding or should guide your operations and enterprise can be very useful, indeed perhaps also necessary for your informed and wise participation.

That’s because there is one thing worse than backing the wrong lead horse.

Following it.