Should Our Professional Ethics Ever Change?

On the one hand, these preoccupations and occupations are in so many ways so different from each other that it seems sensible to create different guidelines for different domains.

Surely, the ethical issues and challenges inherent in animal experimentation are very different from those germane to client confidentiality in law or psychiatry, plagiarism in art, or to the problem of your kids’ mugging other kids for their Nikes.

On the other hand, since the mass of humanity seems quite satisfied with one short list of commandments or another as their moral compass, rudder, sail and anchor, why not simply apply those to all domains of life, fleshing them out with details in specific instances in specific arenas of life where necessary? “Thou shalt not bear false witness” imposes a reasonable restraint on all domains of human activity and interest—doesn’t it?

The ‘Big Codes’—Complete and Eternal?

If the reply is that the rules as stated, e.g., “love thy neighbor as thyself” or “the greatest good for the greatest number” or “make a pilgrimage to Mecca” are only examples, are either too broad or too narrow, too general or too specific, too vague or too abstract, too arbitrary or too controversial, then their claim to completeness, clarity, consistency, compulsoriness and cogency becomes debatable.

That’s too bad, because it would be wonderful if such compact universal moral and ethical codes could be applied to everything from the ethics (or lack thereof) of Hollywood casting-couch producers to demands for war reparations, organ donations and hostile corporate takeovers.

In particular, one of the tremendous advantages such universal and widely accepted codes (the “Big Codes”) have over others is that apparently they never change or need to. So, if they also covered all ethical issues, problems, dilemmas and situations, they presumably would do so forever, without ever having to evolve,be updated or—God (literally) forbid (!)—scrapped.

With respect to this question of change, including evolution, codes like the Ten Commandments differ from the code of ethics governing medicine. The Big Ten are regarded as literally and eternally chiseled in stone, whereas bioethics is not only a relative newcomer, but one that is forced to be agile—ever adapting to changes and advances in technology, public sentiment, medical discoveries and reformulated research protocols and statistics.

It may be argued that the traditional Big Codes don’t even have the requisite concepts to deal with the many of the thorny issues spawned by modern technology: If brain death is the test for expiring, is it morally right to harvest the organs of someone who is brain dead, but breathing? Which commandment covers that—in any way at all, however vaguely? “Thou shalt not kill”? But is it killing? How can you kill a dead person? (On second thought, maybe “Thou shalt define ‘dead’ such that thou dost not kill” could work.)

This kind of example suggests that the most fervently espoused moral codes are probably incomplete or seriously vague. What revered moral principle can address the question of whether it is right or wrong to post a humiliating photo of your boss on your Facebook page? What about the bioethics of stem cell research or cloning of your favorite child? If the Big Codes are silent on such matters, is that in order to stimulate our moral imaginations and spark exercise of free will?

So, instead of asking whether or how we can base our professional codes on any of the Big Codes, perhaps we should reverse the question and ask whether we should be reformulating our Big Codes to more closely resemble the historically evolving codes of business, research, law, science and teenagers—although, it is to be hoped, with better guidance, direction and judgment than that of some adolescents. (General acceptance of the idea of “evolution of the Ten Commandments” is wonderfully ironic, given their adherents’ widespread presupposition that evolution does not exist.)

The (Un)Eternal Wisdom of the Professional Greek

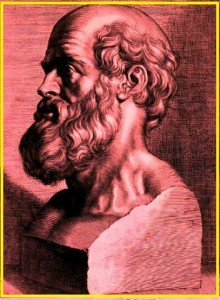

As for further demonstrating the mutability and evolution of professional codes, if it is not already clear that technology, science and culture (to name but three influences) are forcing at least debates about changing and formulating our professional bioethics, if not having already forced the changes, compare the original Hippocratic Oath physicians were sworn to uphold 2,500 years ago with the modern standard.

One barely gets started reading over the original Hippocratic oath (named after, but not written by him) when, boom, the first abandoned principle appears: Referring to a physician who trains the initiate, the oath stipulates the following duty toward one’s teacher of medicine:

“…to look upon his offspring in the same footing as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they shall wish to learn it, without fee or stipulation.”

The closest approximation to that in the modern age would be the concept of the pro bono family doctor, but only if “family” were to mean “the family of my teacher”. In any case, the requirement clearly did not anticipate the exposure to numerous teachers typical of a modern medical school education.

Attempting to honor that part of the oath would transform a young intern’s exhaustion into utter collapse, even though some would argue that a physician’s 21st-century fees might cover the extra expense of another twenty physician families.

Equally un-modern is this: “…in like manner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion.” Perhaps pharmacists can claim an exemption on the grounds of not being physicians. As for physicians, they may try to wiggle out of this one by reason of difference of methods used.

In any case, it is reasonable to assume that Hippocrates was, with respect to this issue, as concerned about the end as well as with the means—a professional moral sentiment not universally evident these days.

The degree to which the modern Hippocratic Oath diverges from the original is clear from this excerpt from a 2001 PBS-Nova report, “The Hippocratic Oath Today ”:

“According to a 1993 survey of 150 U.S. and Canadian medical schools, for example, only 14 percent of modern oaths prohibit euthanasia, 11 percent hold covenant with a deity, 8 percent foreswear abortion, and a mere 3 percent forbid sexual contact with patients—all maxims held sacred in the classical version.

The original calls for free tuition for medical students and for doctors never to ‘use the knife’ (that is, conduct surgical procedures)—both obviously out of step with modern-day practice.

Perhaps most telling, while the classical oath calls for ‘the opposite’ of pleasure and fame for those who transgress the oath, fewer than half of oaths taken today insist the taker be held accountable for keeping the pledge.”

As for the oft-quoted phrase—associated with, but not actually verbatim found in, the Hippocratic Oath , “above all, do no harm”, even if that principle has officially or nominally been retained, the medical profession has created a little moral wiggle room for itself.

Such leeway has been created by describing and obscuring some such physician-induced harm—hopefully unintentional—as “iatrogenic”, i.e., “caused by medical treatment: said especially of symptoms, ailments, or disorders induced by drugs or surgery” (Merriam Webster), thereby tacitly and subtly lumping physician-induced harm together with other “natural” perils.

Given the coinage of “iatrogenic”, with roots as Greek and ancient as Hippocrates, modern medicine has risen and adhered to at least one more crucial standard set by the original oath, thereby resisting change on at least one more front: The modern physician, like his ancient counterpart must, in prescribing for and treating all patients,….

…“Make sure it sounds like Greek to them.”