Aquacommuting: A Different Way to Work

Air Force One, the presidential jet, approximates this, but, eventually the president ends up back in the Oval Office. Even the president doesn’t have a full-time mobile office. So, who does?

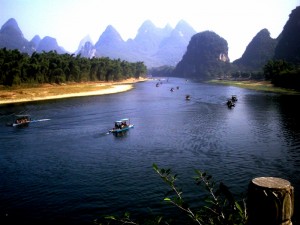

As I reflected on this photo I took a couple of days ago at the Li River in Yangshuo, China, the ferrymen piloting the sightseeing rafts plying the river inspired the thought of a truly mobile office, and of a unique work style: aquacommuting. Those among the ferrymen that are entirely self-employed do approximate the concept to a degree: Their clients board the raft at one location, disembark at another—just like clients coming to an urban office for the services offered there.

True Aquacommuting

The approximation to a purely mobile office becomes perfect in cases in which the boatman lives a few feet from or on his boat and therefore does not have a commute (unless taking a few steps counts as one). On analogy with full-time telecommuting (or teleworking), full-time aquacommuting should mean not commuting at all, instead, working full-time from a floating or cruising home office. Hence, a Li River houseboat that doubles as a river tour boat nicely exemplifies the mobile office, specifically, the office of an aquacommuter.

Presumably, and at the other end of the socioeconomic scale, any Russian oil billionaire who works full-time or part-time from his yacht is a prototypical, albeit super-upscale aquacommuter, with his various luxury cabins, deck, etc., as his offices.

(The leveling similarities between the aquacommuting ferryman’s and the oil billionaire’s work styles illustrate that sometimes, indeed, “less is more” or nearly as good as more—at least with respect to the professional autonomy and “job mobility”, in the present sense of that term, that they both enjoy,).

AQUACOMMUTING IN STYLE

According to merriamwebster.com, an office is “the building, room, or series of rooms in which the affairs of a business, professional person, branch of government, etc. are carried on”. So, allowing that compartments, cabins and rooms on a boat are offices, an aquacommuting ferryman or billionaire can be said to have a mobile office.

How to Aquacommute: the Way and the Costs

Although you are virtually certain to be neither a humble raft pilot nor a billionaire yacht captain, you can consider switching to an aquacommuting work-and-life style.

The steps are simple:

- Sell your house, condo or apartment (an option that dramatically reduces the financial burden)

- Buy an affordable yacht

- Work from and live on the yacht

What is this kind of aquacommuting going to cost you? According to a May 7, 2000 article, “The Cost of… Owning a Yacht”, posted in the UK’s Guardian newspaper, a fully-equipped and serviced yacht, with sleeping quarters, can be expected to cost a total of £312,000 –or, rounded off to the dollar, US $500,000, for a decade of yachting (and, by implication, aquacommuting, assuming no special work-related additional costs).

Here’s the Guardian’s breakdown:

Cost of a yacht over 10 years, excluding inflation:

- (New) Boat £250,000 ( US $400,000)

- Mooring £35,000 (US $56,000)

- Maintenance £15,000 (US $24,000)

- Diesel fuel £5,000 (US $8,000)

- Insurance £7,000 (US $11,200)

Total: £312,000 (approximately $500,000/decade or $50,000/year) @ £1=US$1.60

One UK skipper, itemizing his expenses for 2012, reported inflation-sensitive expenses (apart from one-time repair outlays) of

- £2,520 marina berth – (£420/month)

- £250 insurance

- £300 fuel

- £400 Engine parts and spares and repairs

The $18,000 he spent over two years on his boat’s engine, sails, windlass and anchor were unusual, and probably a reflection of the age of his boat, built in 1983. So, the Guardian estimate of £15,000 ($24,000) over 10 years seems reasonable.

Over a 10-year period, that comes to a total of £25,200 ($40,000), £2,500 ($4,000) and £3,000 ($4,800), respectively—actually, for each item, substantially less than the Guardian 2000 estimate. (Of course, given historical fluctuations in the price of oil and other fuels, at different times and locations, boat fuel prices may vary considerably).

The Income Required for Aquacommuting

Working with these estimates, and assuming you sell your home (which means no mortgage to pay thereafter), but do not apply any of the proceeds to the purchase of your yacht, my guesstimate is that you will have to clear about $60,000-$70,000 annually, after tax, to cover the £31,000 ($50,000) in the listed annual yacht-related expenses plus other costs, such as food, wireless services, health insurance, interest payments (if the boat is purchased with a loan) and skipper accoutrements, such as spiffy caps.

This calculation assumes at least another $1,000/month, especially since health insurance—even normally inexpensive health insurance for Canadians ($60+/month)—can become pricey, particularly so, if you are at sea for more than six months, in which case, Canadian provincial health insurance coverage (a prerequisite for inexpensive supplementary private health insurance for Canadians) will be lost in virtue of deemed non-residence.

If you apply the proceeds of the sale of your home to the yacht purchase, your required income will drop, perhaps dramatically, e.g., in the best-case scenario that has you clearing $400,000 (£250,000) or more for your house, condo or apartment—in which case, your 10-year payout becomes only $10,000 (£16,000) per year.

What’s more, since the mooring charge is the second biggest expense after the yacht purchase, you may be able to get by on an even much smaller income, if you can avoid for-fee mooring, while allowing for occasional docking only for refueling, taking on supplies or clients and sightseeing. Is this actually possible, without owning your own island? I’m no sailor, but I know who you should ask.

Any Li River raft pilot.

Â

Top Photo by Michael Moffa