When and Why the Good Guy Quits the Company First

One of the two antagonists is a “good guy”—ethical, responsible, reasonable and pretty much blameless.

The other is the start-up’s Hound from Hell: deceitful, manipulative, dishonest, unreasonable and pretty much to blame for the mess he’s trying to pin on the good guy and willing to exacerbate by passive aggressive obstruction, covert sabotage and overt attack.

With the unalterable entanglement and battle lines drawn with no truce or negotiation in sight, it’s clear that one of them is going to have to go, if the company is to prevent serious in-house damage to its operations and morale. Because of contractual partnership arrangements, firing is not an option, nor, for now, is a stockholder’s meeting that might sort things out.

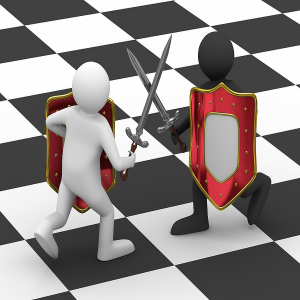

The likeliest, if not only solution, is that one of them blinks and quits. The question is which one is it likely to be—the White Knight good guy, or the Black Knight villain?

A Real-Time, Real-World Case

This is neither a hypothetical question nor hypothetical situation: I just got off the phone coaching a $120,000-a-year IT good-guy friend of mine about how to deal with a bad-guy business “partner”, when the third has backed off from the feud and retreated into his own private Switzerland state of mind.

There are many details in this head-butting between my friend and the organization’s single Axis of Evil spinning a dark web of intrigue and innuendo, e.g., the Black Knight’s fabricated, unsubstantiated and vague accusations about my friend’s performance and professionalism hammered with a question-begging demanded “action plan” that requires addressing dozens and dozens of “complaints” nearly double Luther’s 99 Theses nailed to a church door. (Part of what makes that so insidious is that the allegations include lots of the “explain why you haven’t stopped beating your wife” sort, leveled at a bachelor.)

But knowing such details is not crucial, since an examination and analysis of the White Knight-Black Knight (a.k.a. “White Hat-Black Hat”) dynamics and their probable outcome can be performed at a much more abstract level and with broad relevance to such good guy-bad-guy smack-downs—much as a game of chess can be understood without specifying the color and material of the pieces and board, or how long each move took.

The Trapped White Knight

What I told my White Knight friend is that he must be very, very careful not to be manipulated into quitting just because he is a good guy. Sure, many good guys have a stomach for a fight (especially my friend, who, already as tough as unhammerable Viking nails, has recently taken up full-contact sparring in a gym ring).

His “kryptonite” (to switch imagery) and key vulnerability is, ironically, also his strength—namely, that he is indeed a good guy, with a conscience, a distaste for conflict, a commitment to reasonableness, a well-developed sense of responsibility and a regard for “the greater good”.

In contrast to this, his nemesis is much less vulnerable (given the neutrality of the other partner), much as evil armies are less vulnerable than moral ones, in virtue of the much larger number of tactics, strategies, principles (or lack thereof) and weapons available to them, e.g., use of banned gases, bio-weapons and innocent civilian targeting.

Even though victors always see themselves as “good” or at least “right”, some victors are better than others, if the White Knight standards of goodness and rectitude I’ve described here are accepted. Moreover, despite the broader range of tactics available to Black Knights, good often does triumph over evil, often because the White Knights have access to greater resources (natural, technological and/or political, if not supernatural, i.e., assistance from their supplicated God(s))—in no small measure in virtue of what they identify as their virtues, e.g., the virtues of valuing fairness and freedom (whether of expression, religion, thought, research, invention or markets).

Whether the Black Knight is a business partner or an escaped SS officer, he is far likelier to believe and act as though “the ends justify the means” than is the good guy. This means that tit-for-tat retaliation by the White Knight is less likely than from the Black Knight and that the Black Knight retaliation can be of a form the White Knight would never morally allow himself to inflict.

That “asymmetrical” conflict means that, in a war of attrition, with both sides having otherwise identical resources and without allies, the bad guy has the edge and need only wait until his preponderance of retaliatory or “first-strike” capability wears out his ally-less adversary.

Moreover, it is virtually certain that the White Knight is likelier to quit the company from “moral principle” than the Black Knight is, e.g., out of moral and psychological regard for the “good of the company”, as operations become collateral damage of the endless feuding. The grave danger for the good guy is that such moral concerns may play into the hands of the bad guy and play out as a “do unto oneself before doing unto the company” self-sacrificing martyrdom.

Because the moral high ground is a handy perch from which to jump into the unemployment abyss, it can easily provide a tempting, if not compelling rationalization of a decision to quit, actually based on simple fatigue or loss of confidence or stomach for a fight.

More Traps

Similar traps and consequences, including the likelihood of quitting first, can be identified in connection with all the other attributes of the White Knight:

Responsible: This is a corollary to the propensity to act for the “greater good”. The Machiavellian Black Knight will not be encumbered by any sense of “responsibility”, being more preoccupied with his next response.

Reasonable: Only a subset of the rational, reasonableness can be a White Knight’s Achilles’ heel, given that the only rationality that the Black Knight is constrained by or committed to is cold calculation. Consider the nuance of “reasonable”—It has built into it the strong suggestion, if not requirement, of a willingness to negotiate and otherwise be flexible, in addition to acting in accord with reason.

Blameless: Like acting for the greater good, feeling and being blameless can trigger a martyr-complex (however fleeting) and the impulse to quit before the Black Knight. Here too, the moral high ground of martyrdom and self-sacrifice may tempt the White Knight to ride his noble steed over the cliff, a la Thelma and Louise, as a rationalization of a lack of energy, courage, etc.

Allied Moves

Of course, these Knight dynamics change completely once the 2-person game gets complicated with alliances and becomes an n-person game (n>2). In many scenarios, the Black Knight quits first, before being driven out by the Allies. in other scenarios, the White Knight quits sooner, for the same reason. Hence, a key pre-game or mid-game move is to choose whether to populate your board with useful and helpful allies to alter the balance of power.

As for my good guy friend and for now, merely being alerted to the traps has helped, which, I guess, makes me an off-board ally…

…on board for the game.