Too Alien for the Workplace?—Robots, Expats and Language Learners in the ‘Uncanny Valley’

At best, you will then become confused, or, at worst, terrified. Robot evolution has, it seems, already reached that point and moment, according to reports about research into what has been called “the uncanny valley” of perception—a phenomenon and moment fraught with important implications about robot penetration into our workplaces, kitchens and streets.

A concept and phenomenon in the field of human aesthetics, “uncanny valley ” designates the hypothesis and observation that when humanoids look and move almost, but not exactly, like real, normal human beings, the response is revulsion [or at least some profound unease].

However, as I shall argue below, there is more than one cause of this kind of unease, including an analogue of the phenomenon of the uncanny valley that characterizes responses still-human expat staff may encounter overseas, language learners can expect from native speakers and toy makers can expect from kids, as that which is perceived more and more closely comes to resemble “the real deal”.

The Uncanny Valley Variables

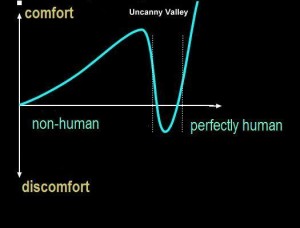

Research and anecdotal evidence suggests that when degree of warm, fuzzies-comfortable “psychological-familiarity” is graphically mapped against “human-likeness”, the two variables increase together—but only up to a point. Beyond that, the comfort level doesn’t merely begin to drop; it goes negative, below the zero baseline, which means revulsion, disengagement, estrangement and basically feeling weirded-out.

The case of the zoo panda commenting on a Wall Street Journal analysis perfectly illustrates this phenomenon, even though robotics has nothing to do with it: “Cute” morphs into “creepy”, or maybe even into “competitor” as the panda become more human-like, indeed, too human-like, in at least one respect.

Two Different Phenomena?

An international team led by Ayse Pinar Saygin of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) is reported to have come up with the explanation of the uncanny valley effect, of why affectionate familiarity decreases as resemblance to humans becomes more perfect.

What is very interesting is that, if that explanation is not only germane and correct, but also the explanation of the uncanny valley, rather than just one among other valid alternative or co-explanations, the uncanny valley may, before long, be left behind by robots as they become even more humanoid, rather than become their base of permanent exile, and once again ascend into the zone of fond familiarity and warm welcomes.

Here’s why: Put as simply as possible, the Saygin team research has been reported as suggesting that the plunge into the uncanny valley occurs with the onset of a severe perceptual conflict between the human-like features of the robot and its inhuman or imperfectly human movement. Smooth latex skin, blinking blue eyes, soft hair, but spasmodic movement—combined, these create unease, as the Saygin experiments discovered.

But, as I see it, this has nothing at all to do with the uncanny valley. The problem with a lurching, yet beautiful gyndroid [female humanoid robot] is not that it has become more or too human; instead, the unease is caused by the perception of the gyndroid as not human enough.

In retort to this argument, it may be claimed that whether or not this is an unhappy valley phenomenon depends on which is perceived as the “add-on” characteristic: the human-like features or the jerky motion.

If human-like features are perceived as added to jerky motion, it is reasonable to expect less of a shocked, confused or wary response than if what is primarily perceived as human-like is then seen to move abnormally.

One astute comment regarding the report suggested that the uncomfortable response to a spasmodic robot may be the same as that to a human moving jerkily—namely, that something is wrong, e.g., a seizure, stroke or neurological damage.

In both instances, the unease is caused by a sub-normal or abnormal performance gauged by normal human standards, not by a performance that is too good, too normal, too convincing.

Parting of the Panda and Robot Ways

It is in this respect that panda and robot part ways: Whereas our being weirded out by a hedge-fund managing panda is due entirely to the uncanny valley effect—namely, a plunge in comfortable familiarity as the panda becomes more perfectly human [by speaking perfectly, despite an imperfect humanoid appearance], the phenomenon Saygin’s team is reporting is quite the opposite, being about reported unease because of insufficiently normal human behaviors on and by the part[s] of robots.

As I understand it, the descent into the uncanny valley is the result of a too close, albeit not an overall perfect resemblance to normal humans, rather than the result of an insufficient resemblance or a resemblance to a “damaged” human. The Saygin research, as reported, is about and has implications for the latter, not the former.

To see this, consider this summary of the research, in the November 23, 2013 Daily Telegraph article, “Robots, the ‘Uncanny Valley’ and Learning to Love the Alien” :

“Saygin and her team conducted an experiment scanning the brains of 20 subjects aged 20 to 36 while they were looking at three different things: a human, a mechanical-looking robot, and a human-like robot.

Interpreting the results from the fMRI scans, the researchers suggested that the cause for the valley is a mismatch between at least two neural pathways: that of recognising a human-like face and that of recognising different kinds of movement”. [Underlining is mine, for emphasis.]

The main thing that the panda uncanny valley and the Saygin research conclusion have in common is the element of incongruity as a causal factor in unease.

But there is a world of difference between the incongruity of abnormal perfection of an isolated feature [the perfect human speech of the panda] and the incongruity of abnormal imperfection of the whole [the spastic humanoid].

Abnormally Perfect vs. Abnormally Imperfect

The difference between these two distinct disengagement phenomena is important, because of what it implies about future acceptance or rejection of workplace robots [as replacements or helpers for working humans].

On the uncanny valley familiarity + human-likeness interpretation, elimination of spastic movements and other non-human behaviors and features of robots can only exacerbate and accelerate rejection of robots as too “creepy” or “alien”, in virtue of their becoming more human-like, but not completely so.

However, the Saygin interpretation says nothing about what happens when robot movement becomes as smooth as robot skin. That and common sense leave the door open to renewed and greater acceptance of robots in the workplace, home and in our communities, in direct contradiction to what would be expected from the standpoint of the uncanny valley phenomenon.

The only case in which both interpretations are likely to coincide in their predictions is that in which the humanoid becomes utterly indistinguishable from a real human.

For, in that instance, all incongruity—both incongruous perfection of some feature and incongruous imperfection of another—will vanish, leaving only a perfect, whole human[oid].

Indeed, the Daily Telegraph report clearly suggests that: “However, once movements become even more human-like, the familiarity graph rises again from the uncanny valley; acceptability returns steeply to normal.”

Short of that, they have contradictory implications that presumably will be eliminated asymptotically as humanoid robots become us.

Enter the Expat and Language Learner Unhappy Valley

As asserted above, the unhappy valley effect applies beyond the field of robotics, well into purely human domains—for example, in expat and language learner foreign workplaces.

In both environments, a feeling of comfort with and acceptance of observed performance can and often does follow the contours of the uncanny valley curve. To economize on words, I’ve lumped these together into one example:

An expat manager, since 2012 no longer required to have an “alien registration card ” in hand, starts a new job in Japan. At first, even his sneezes draw compliments about his Japanese language ability. Slowly, he makes headway and becomes somewhat conversant in Japanese. The compliments become more frequent and more enthusiastic.

So it goes, until, one day, he expresses, in perfect Japanese, “The Hegelian dialectic is actually an unstable equilibrium”. Oops—line crossed; he just became a talking, too-knowledgeable panda. Yea, he now walketh in the valley of the shadow of the uncanny.

Why did the compliments end and the unease begin? First possibility: He made Japanese look too easy. When a language is not widely spoken, there are usually only two reasons—either it’s really hard or it’s not very important. Speaking Japanese fluently can get one into trouble—and not only with those who suspect “pick-up artist” or obnoxious show off.

In sociological and bar-stool discussions of “the myth of Nihongo [the Japanese language]”, back in the ‘80s and ‘90s, it was suggested that expat fluency either made the Japanese language look too easy, or on the other hand, made the expat look like a weird “wannabe”—not to be confused with the pungent mustard, wasabi.

The result of that fluency: text-book uncanny valley syndrome. The more perfect his Japanese becomes, the fewer the compliments and the more uncomfortable that progress and near perfection will make some—not all—Japanese.

If that expat manager is also seen as a pampered competitor or rival—with special perks, higher-than-local salary and exemptions from some of the onerous rules of corporate culture, e.g., stifling suit, compulsory attendance or silence at all meetings, the uncanny valley discomfort engendered will be virtually indistinguishable from that experienced in dealing with a too-perfect-for-comfort office robot competing for, if not eliminating, at least one human’s job.

I also observed a reverse uncanny valley effect during my years as an expat in Japan: A group of us met a perfectly fluent and personable Japanese guy whose English was so perfect that it weirded us out, a bit like a demonically-possessed Chucky doll would. How perfect?

Although he had never left Japan, he spoke not only flawless English, but perfect American English with a perfect Texan drawl. How perfect? Certainly better English, better Texan than Dubya Bush—for sure, but why?

So, one minute, he’s into “Red River Valley”. The next stop, Uncanny Valley.

…and a place next to us working expats, too-nearly perfect robots and the talking uppity panda.